Powerpuff

DETAILS MAGAZINE

SEPTEMBER 2001

Photo by Michael Thompson

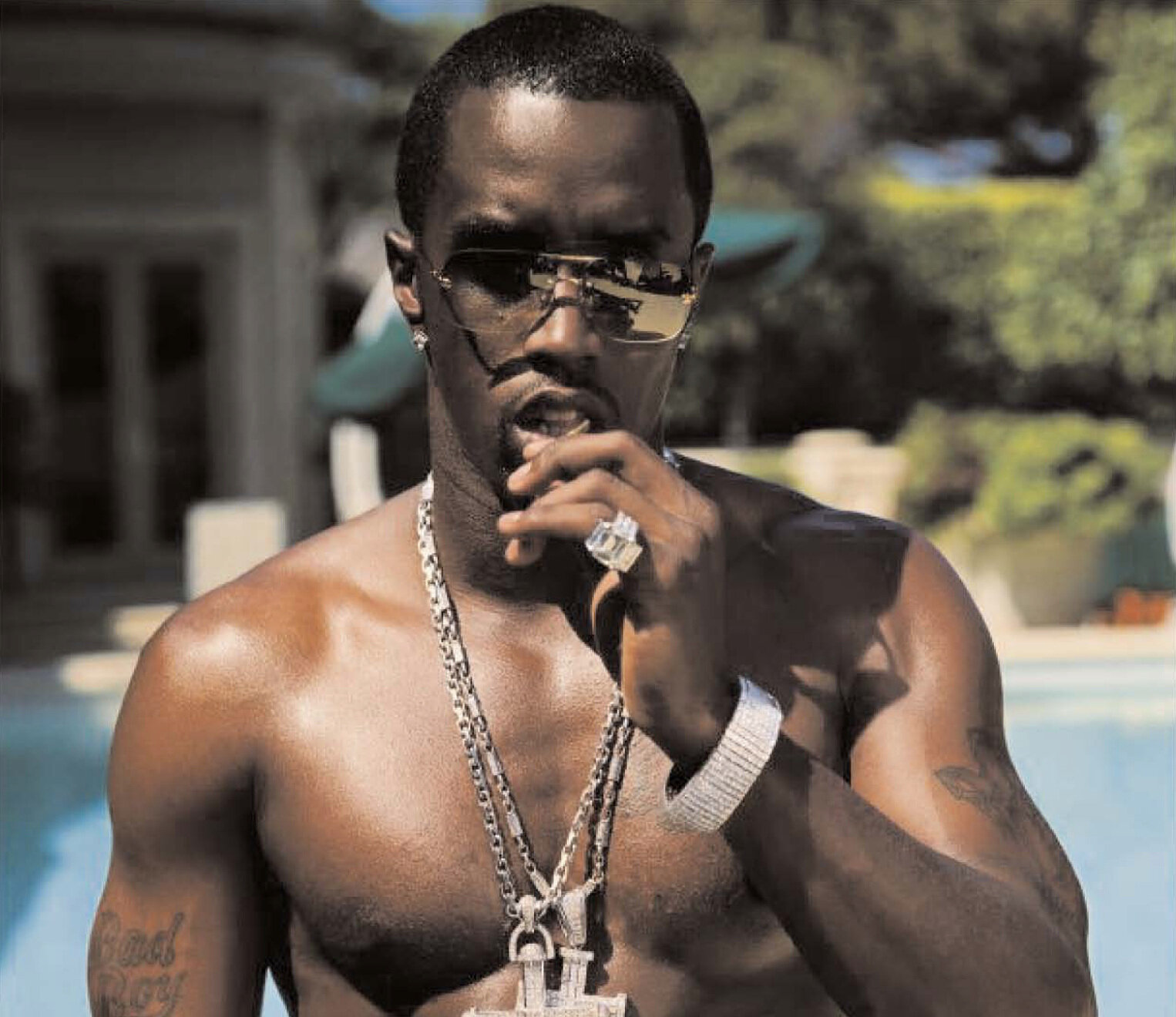

He lost the girl. He lost the rep. He almost lost his freedom. But Sean Combs remains a $250 million master of re-invention: the only playa who could jump from Timberland-rockin’ boy to polo-watching, Hamptons-hopping Gatsby. Now he’s planning his next makeover–if only the haters would stop asking the same damn questions.

“I don’t hate you,” Sean Combs growls as he zips his jacket and gets ready to leave. “I’m just sick of answering your ridiculous questions.”

It’s a little after 11 P.M. on a chilly Sunday evening in Beverly Hills, and Sean “Puff Daddy, a.k.a. P. Diddy” Combs has come to Matsuhisa, an elegant raw-fishery to the stars (Mark Wahlberg is chewing squid in a nearby corner), to plug his latest cultural adventures: a feature-film debut, Made, a new CD, P. Diddy & the Bad Boy Family… the Saga Continues. But against the advice of his media hand-holder—a big-haired woman in tight, sequin-clotted jeans who warned me to “flatter” him—I insist on asking all the wrong questions.

I want to know about the fallout from the Manhattan trial in which he was acquitted of bribery and gun possession; about rumors of an IRS investigation into his Bad Boy Entertainment empire; about his headline-making split with actress-singer Jennifer “J-Lo” Lopez; about the possibility of a flare-up in the bloody East Coast-West Coast rap rivalry, now that Death Rows Records kingpin Marion “Suge” Knight (a Puffy archenemy) is about to be released from jail.

I want to know way more than Combs cares to tell.

I must be a moron.

After all, Sean Combs is not a guy you want to piss off. Previous irritants have been rumored to find themselves lectured to with the blunt end of a champagne bottle. Now here he is, skulking over me in a black velvet track suit and big white sneakers. And here I am, pissing off Puffy.

Things had started well. For an hour, Combs gamely dodged and swatted questions, or simply warned me to back off. He slouched in his chair and poked at the shitake mushrooms on his Chilean sea bass. He ignored me in favor of a steady stream of e-mail dispatches form his silver Motorola two-way pager. But when Knight comes up, he explodes. “If y’all want to know ‘bout East Cost-West Coast, why don’t you ask Suge Knight?” Combs says, clearly rattled, just moments before he stands. “Why don’t you go interview him?”

“Time is money to me,” he says, cocking his head and narrowing his eye—his face a knot of clichéd features has the odd effect of making him look more confused than menacing. He puffs out his chest. “And you wasting my time.”

Combs stands for a pregnant minute scanning the restaurant, with its move posters singed by Robert DeNiro and High Grant, as we look up from the littered table. He appears frozen. It’s ten feet to door. Without a big posse, he seems to realize, it a very lonely stage exit.

The first time I met Sean Combs, he was strutting up the paparazzi-lined red carpet of a movie theater in New York City’s East Village. Dressed down in acid-washed jeans, he’d just beelined to a CNN crew.

“I’m going to savior this day,” he told the camera lens that balmy July evening. “Check out the movie this weekend, and make sure you get the album.” The CNN reporter complimented his QVC sales pitch. Combs laughed sand said, “I want you to have the flavor.” Then he smacked the guy on the ass and joined his Made co-stars, Vince Vaughn and writer-director Jon Favreau.

In the low-budget comedy, Combs plays a gangster who trades Internet stocks by cell phone. The role works because Combs acts against type; he doesn’t flash guns or use violence. Instead, he plays it Don Corleone suave.

“He was really open to poke fun at that image,” says Favreau, who admits he was reluctant to meet Combs—“we didn’t know if he was criminal or what.” In the end, Favreau was struck by Comb’s graciousness. “He could have easily picked a genre piece where he was busting caps in every scene,’ Favreau says.

Sean Combs no long wants to bust caps. He wants to move on. He wants closure, or the media equivalent: to be shuffled out of scandal-du-jour rotation. He wants to forget these things, and tonight, I’m the jerk that who won’t let him.

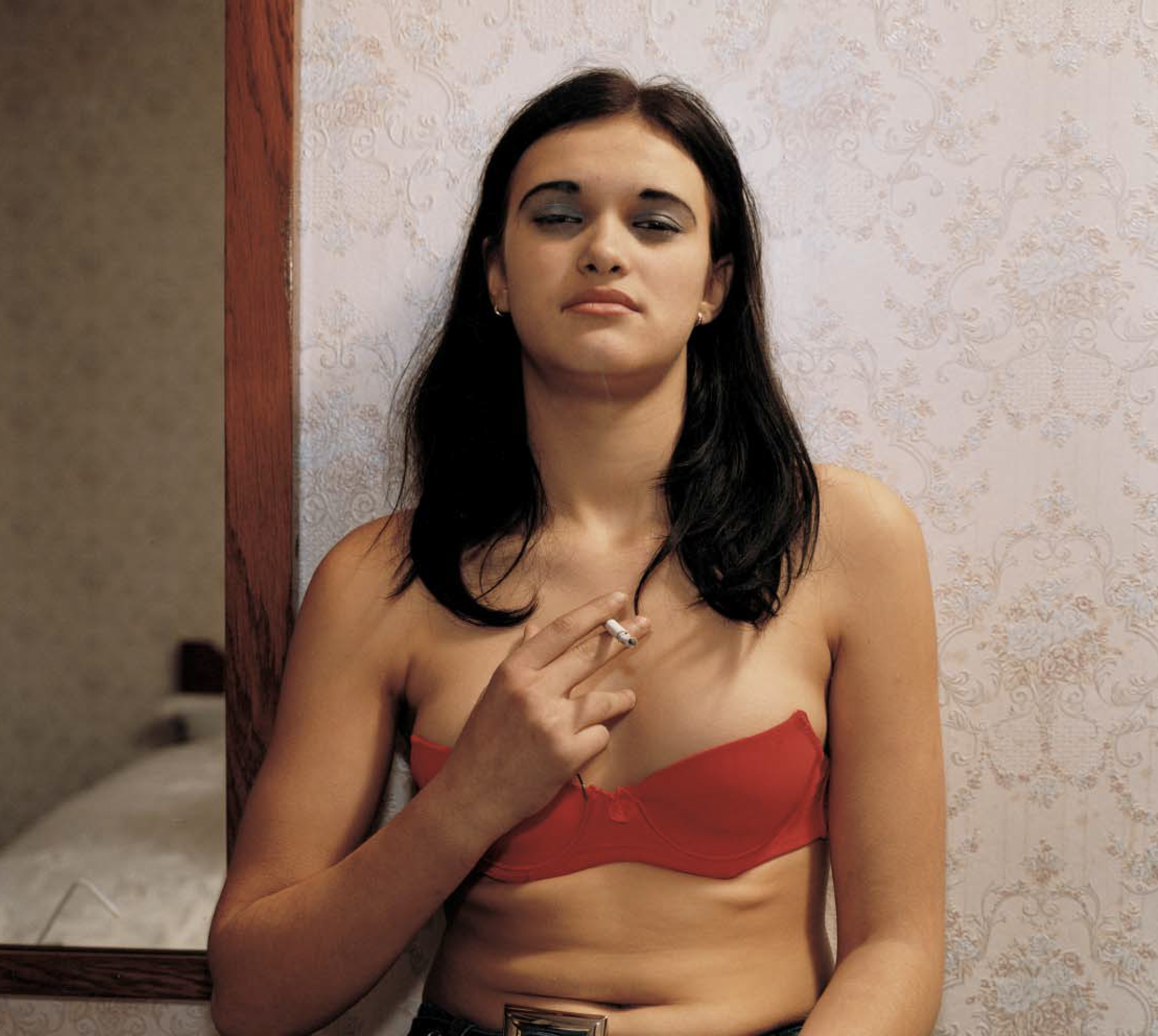

In his active effort to put space between his troubles and his post-trial, post J-Lo life, Combs has been squiring Maltese model Emma Heming, whom the tabloids label a J-Lo look-alike. He’s been partying in Paris, where he caught a late-June Versace show, then rolled off in a Mercedes to two glitzy parties and wound up toasting the sunrise with Heming, Kevin Spacey, Naomi Campbell, Christina Ricci, and Heath Ledger at the foot of the Eiffel Tower.

“I just want to do something of quality,” Combs says, before the dinner drama. “I mean, I already demand seven figures. The money can’t motivate me.”

Money, of course, has always played a motivational role in Comb’s success. His music videos gleam with $300,000 Bentleys (he owns two) and geysers of Cristal champagne, which he sips on the pitcher’s mound at Hamptons softball games. It was Combs who came up with “the new Gatsby” photo shoot for this magazine, hand-picking his outfits (and Heming’s) from sixteen racks of clothes, flying a tie from New York to Los Angeles, and suggesting with a wink, that he pose with a faux-diamond-encrusted gun. (The gun was brought in but never used.)

F. Scott Fitzgerald never imagined a character like Combs, the self-made record producer with street cred, an eye for raw talent, and an ability to aggressively up-market it into his own image. With a white fur draped on his shoulders, he’s burned “ghetto-fabulous” into a brand that includes his Sean John clothing line (which grossed $100 million last year), two restaurants and Bad Boy Entertainment. Such success has earned Combs, 31, a net worth of $250 million, according to Forbes, and made him the most emulated luminary in rap. “Puffy showed everybody the way,” says Russell Simmons, co-founder of Def Jam. “Just about every rapper goes to work every day so they can be Puffy.”

They may covet his success, but few want his reviews. On his last CD, 1999’s Forever, Combs proved an uninspired rapper, straining to be low-key cool in his bedroom whispered asides. The critics panned him. As a result, he has returned to the formula of 1997’s septuple-platinum No Way Out, trading the spotlight with such Bad Boy acts as Black Rob, Big Azz Ko, and Faith Evans.

Asked if the criticism bothered him, Combs lowers his head and stares up through heavy-lidded eyes. “I feel that I’m better when you hear me, then hear somebody else, then hear me again,” he says. “It’s diversity. Some people maybe wouldn’t be able to handle that. I can easily handle that. I just want to get it right. I just want to please people when it comes to making records. But I mean, criticism and all that shit, that don’t bother me. I love it. Because it makes me better. You learn from criticisms. Unless you scared or unless you insecure. I’m a very secure man. Then he adds, not with humility but in a tone of challenge, “Everybody can’t be perfect.”

Combs certainly hasn’t led a perfect life. His name first splashed across the tabloids in 1991 when nine people died in a stampede at a celebrity basketball game he’d promoted. One of his lowest moments came in 1997, when his close friend Christopher Wallace, a.k.a. the Notorious B.I.G, was killed in Los Angeles as Combs sat in a nearby SUV. Though Wallace’s murder was never solved, rumors have circulated that he was killed after Combs reneged on paying the street gang that was reportedly hired to protect him, a charge Combs denies. Then came his toughest-ever legal challenge: the December 1999 shoot-‘em-up at Club New York in Times Square.

Combs was accused of pulling the gun inside the venue after another reveler threw cash in the air, presumably as ann insult to Combs’ reputation as a “playa.” Combs’s friend Jamal “Shyne” Barrow, a Belize-born rapper signed to Bad Boy, fired several shots, injuring three bystanders. He was arrested outside the club with as 9-mm. gun tucked in his waistband, while Combs fled with his driver and Lopez in a black Lincoln Navigator, which was stopped by police after running 11 red lights. Inside, the police found a 9-mm. gun. Combs was acquitted, while Barrow was sentenced to ten years in prison.

Combs’s friends say that he’s eased up and turned more spiritual and family-focused. “I can feel the good energy, and, have mercy, it hasn’t always felt like that,” says Faith Evans, another longtime friend and Christopher Wallace’s widow. “He is much more humble and easygoing. He’s always been a fun guy, but he’s a little more relaxed, to say the least.”

After the high-profile breakup with Lopez this past Valentine’s Day (a few days after he sent her a singing present in the form of Luther Vandross), Combs has also sought to put his heartache behind him. “When you come out of a relationship, it hurts,” he says matter-of-factly. “But your life gotta go on. So you make an album, put out a movie, make some new clothes, have some parities, go to the Grand Prix—you do certain shit, keep it movin’. I mean, everything’s all good. I mean, we still cool. Eveyrbody’s all right.”

If Conmbs is bitter over the past year, it doesn’t come across on his CD, which was recorded in Miami after the trial. There are a few veiled references to the gun case, but not much else; overall, it’s an upbeat party disc.

“To be honest, I don’t even think about the trial,” Combs says. “I can’t sit here an obsess. I’m just living a positive life in celebration, if anything, of having a good time. I don’t have no scorn or revenge. I’m just loving life. I guess it al made me appreciate life more.”

That life seems to be as complicated as ever. In the past few months, Combs has been plagued by reports that his Bad Boy outfit is under investigation by the IRS for possible unreported business earnings, and that Combs himself is the subject of a Las Vegas Police probe looking into alleged gun possession. The IRS ad Las Vegas Police have both refused to comment.

Combs has already said that the IRS has failed to find wrongdoing in at least four previous audits, but he says he knows nothing of a new inquiry. Meanwhile, an investigator with knowledge of the Las Vegas case confirms a probe is under way.

When pressed about these reports, Combs bristles, leaning back in his chair and eying me with disdain. “When I call my lawyers and ask if there are probes, they say no,” says Combs. “It’s ridiculous to say there are investigations goin’ on. Come on, man. I don’t even have time for all that.”

Combs has found time to put out one high-profile fire, paying a jailhouse visit to his former co-defendant and protégé Barrow, 22, who has publicly blasted Combs, telling a Village Voice reporter “there are no boundaries to what [Combs] would do to exonerate himself.”

Combs says that he’s paying for media-friendly lawyer Alan Dershowitz to handle Barrow’s appeal. But Combs doesn’t particularly care for this topic; he turns testy as he continues to defend himself. “It ain’t like we in no motherfuckin’ big drug-conspiracy case,” he says. “I mean, what am I doing? I’m not turning state’s evidence on nobody. Come on, man. I’m mad I’m sitting there in the first place. But I’m not trying to do anything to hurt anybody. It’s an unfortunate night. I know he didn’t mean to hurt nobody. It was something we all wish didn’t happen, him shooting in the air. We feel it was out of self-defense, and that’s something we’ll stand by. We fully support him. And that’s about it.”

More problematic for Combs is the parole of Suge Knight from prison this summer. The fearsome and combative Knight, who once reportedly dangled a rapper off his apartment balcony, publicly belittles Combs for his dandyish ways; he believes Combs may have played a part in the murder of Knight’s one-time star artist Tupac Shakur, who was shot to death in Las Vegas in 1996 (a point that Combs denies). Police there believe Shakur’s murder was the result of a bloody feud between East Coast rappers such as Combs and Wallace and West Coast counterparts such as Knight, Shakur and Dr. Dre. Knight’s release could put Combs in danger.

Combs dismisses such talk as nonsense, even as he’s visibly shaken by the idea. “Ain’t nothin’ gonna flare up,” he says, his voice rising. “Somebody getting out of jail, that ain’t got nothing to do with anything. Here wasn’t no East-West thing. That was shit. I guess that’s the way the media likes to put it.”

With that, Combs turns to his publicist and says, “I tried, you know what I’m saying?” He turns back to me and says coolly, “It was good. The interview’s over.”

Then he stands up and unleashes a bitter litany before assessing his path to the door. Finally, he walks away, out to the chilly Beverly Hills night and the black SUV waiting for him at the curb.”