Congo War

DETAILS MAGAZINE

MAY 2004

Photo by Kevin Gray

Joseph Kabila, the 32-year-old president of the Democratic Republic of Congo, is the world’s youngest leader–and his job isn’t exactly a walk in the park. After a long civil war that left nearly four million dead (and his father assassinated at his desk), Kabila faces a fragile cease-fire, a cabinet of former enemies–and attempts on his life. As the country’s first democratic election in more that 40 years approaches, can the untested Kabila survive?

TO SAY IT’S HOT IS A JOKE. IT’S BRAIN-FRYING JUNGLE-HOT. IT’S GET down-on-your-knees-in-the-street-and-beg-forgiveness hot. The humidity alone crushes you. It’s like wearing a dead Labrador around your neck on an August day in Georgia. When I step out of the air-conditioned lobby of Kinshasa’s Grand Hotel in a suit and tie and climb into a sunbaked Honda, a searing jolt sizzles through my spine. And before we hit the bottom of the driveway, I’m soaked to my socks.

My driver, Jean Matadi, is 38. He’s been working the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo for two decades. He was here seven years ago when the hotel was packed with dictator Mobutu Sese Seko’s armed and paranoid ministers, plotting escape routes as Laurent Kabila’s barefoot rebels approached.He was here three years ago when President Kabila was killed by a bodyguard.He was here last year for the cease-fire that ended a civil war that claimed more than three million lives. The settlement elevated four political and military rivals to the role of vice president—each with 108 machine-gun-toting bodyguards in tow. And he’ll be here in three weeks,when rebels will attempt to assassinate the current president and plunge the country back into chaos.

“The government is bullsheet, the politician is bullsheet,” says Jean as we’re quickly snarled in traffic. Like every other driver for hire at the Grand, Jean has no AC.A father of eight, he is a playboy who dresses in rayon disco shirts and thick gold chains, and obsessively nibbles cola nuts,which taste like chalk and produce a scalp-crawling cocaine buzz.At another sweltering stop,we watch as a few slouching policemen shake down Westerners for cigarettes and beer money. Then the polio victims on their hand-cranked tricycles swarm our car, the albino beggars bobbing behind them.

Despair is a natural response to Kinshasa. The city lies just south of the equator, 220 miles inland from the Atlantic, on a fat, muddy bend in the Congo river that looks like a kink in someone’s intestines.At night, displaced soldiers rob travelers. By day, the poor beg outside newly opened banks and armed guards patrol air-conditioned supermarkets. Kinshasa has no public transportation, so thousands line the roads, waiting to cram themselves into the open trunks of overheating sedans.With no work,men roam the dusty streets in a motley retail parade, hawking children’s-bike tires, doll heads, baggies of water. Skinny boys balance pallets of cigarettes and condoms on their heads; old men run copy machines hooked to street lights. Amid rubble-strewn homes, children bathe outdoors while fires burn in the street. And the city’s plantation bosses and bureaucrats glide past in their Mercedes coupes, up to guarded mansions in the tropical hills.

“Everybody’s crazy,” says Jean, yelling over the street noise and shaking his pinkie-ringed hand at the parliament building. “They fight for themselves. They take oil, mines, the food. The small, he is nothing. The population is crying. They have no job, no food. Hospital is very expensive. No money, you die. You sick, you have money, okay. Is a joke.”

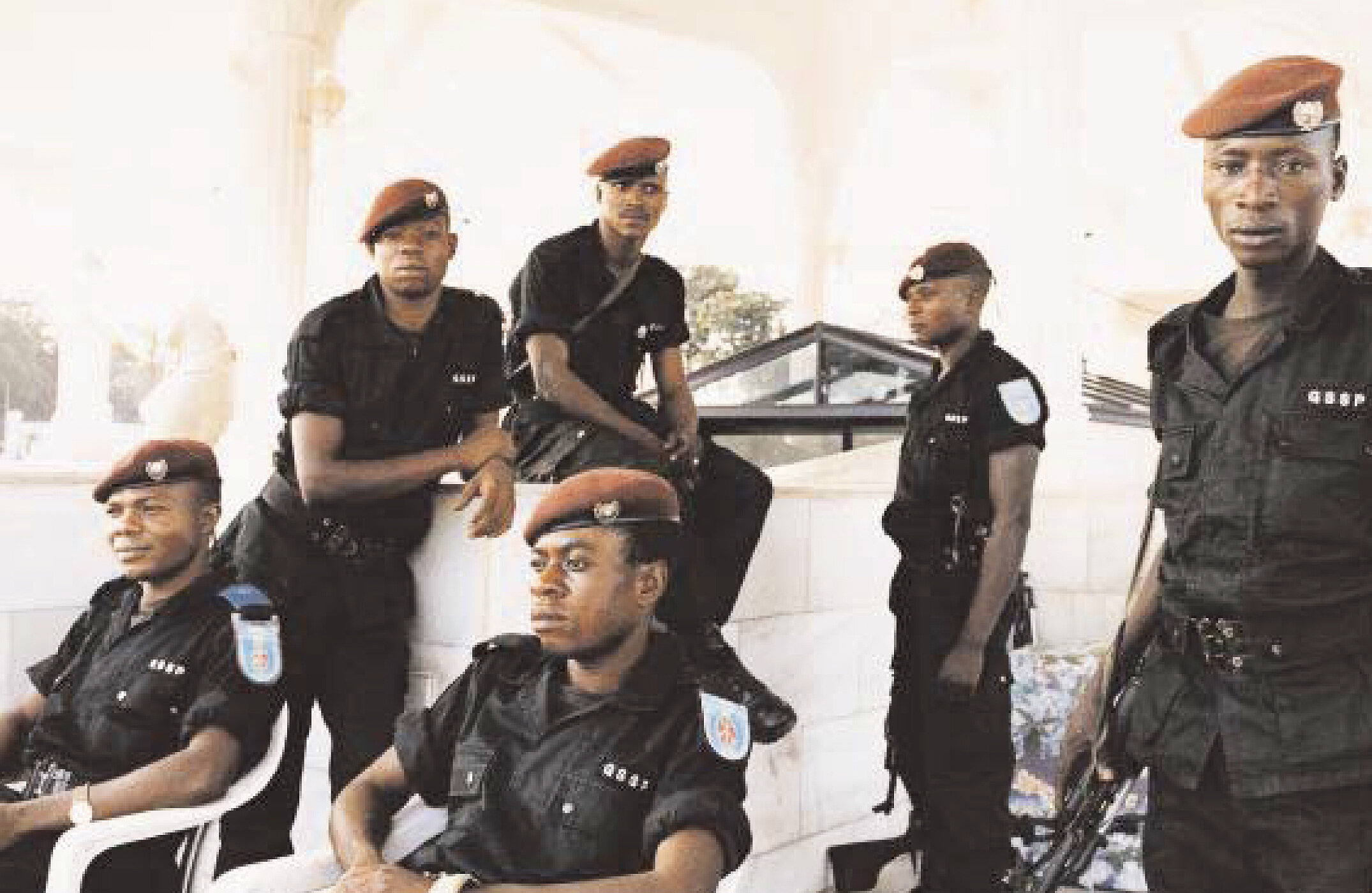

The atmosphere in the capital is prickly. One vice president keeps an escape helicopter parked on the lawn of his riverfront offices. Most ministers travel with a truckload of soldiers cradling grenade launchers. When I try to use a bulky satellite phone,three guardsmenskulk over,hands on their chipped gun barrels, and accuse me of being an “agent.” A few unpleasant moments pass before I realize they only want a payoff,just enough for a 40-ounce Primus beer, about three bucks.

I’m here in late February to interview Congo’s besieged president, Joseph Kabila, but it’s turning out to be a poor day for him to meet the press: Reports of atrocities along the Rwandan border are flooding into the U.N.’s Kinshasa headquarters. A militia leader by the name of Cut Throat has killed 100 villagers; his teenage soldiers are said to be slicing off their victims’ penises for talismans and ceremonially drinking their blood. A U.N. observer has been shot farther north, near the Ugandan border. These fresh conflicts bode badly for Kabila’s claim that he is in control, a situation worsened by a new round of political infighting that threatens to topple his fragile transitional government. The U.N. has mandated that Kabila and his political partners hold a democratic election in 2005. Yet the nation’s permanent constitution remains unratified, and no election law has been passed;the parliament is bogged down in a salary dispute.

It remains to be seen whether Kabila—who will likely face down his four vice presidents—can hang on. The world’s youngest head of state, Joseph Kabila, 32, assumed the presidency after his father’s death. A Marxist who pledged reform, Laurent Kabila had overthrown the infamously brutal Mobutu in 1997. But ethnic battles with neighboring nations—abetted by Kabila’s oppressive regime and vicious scoresettling— sparked a five-year civil war that engulfed the nation.Now the burden of peace has fallen to his son, a man whose only professional experience is serving, with dubious results,as a general and chief of staff of his father’s army.

Observers hope Kabila will prove to be a new breed of African leader, one who will help solidify an African renaissance. His youth alone has made him a star among Congo’s small young affluent class. He drives a black Mercedes G-500 SUV, blasting reggae,and flies in a private plane.He shows up at the local stadium in jeans and Air Nikes to hang with the city’s soccer team. Young women scream as he passes by. (He has a 4-year-old daughter but remains a committed bachelor.)

Elegant and compact, with doe-like eyes and a methodical mind, Kabila has won many friends in and out of Africa. In place of his father’s bellicose Marxism, he talks of “transparent democracy” and “open markets.” In place of Mobutu’s strongman machismo—the leopard-skin hats, the pricey cigars and crocodile shoes—he is genteel in Wall Street power blue. Kabila has indeed managed to liberalize the economy, create new investment codes, and rescind regulations that had hamstrung investors. All this is part of an effort to assuage the International Monetary Fund,which holds the purse strings to some $10 billion in expected aid, and to attract Western investors to the country’s considerable natural resources:diamonds,gold, oil, copper, rubber, precious wood, coltan (an ore used to make computer and cell-phone capacitors)— and uranium.

But Africa has long suffered its share of reformers gone bad. Though Kabila has neutralized most of his father’s hard-liners—the very people who elevated him to power—his methods have sometimes veered toward the Machiavellian. And there is a darker side to the young president,one that observers say recalls the ruthlessness of Mobutu or the vengefulness of his father.He refuses to discuss his father’s murder, but 30 men have been tried by a military tribunal, found guilty, and sentenced to death over the protests of human-rights groups. Since January, half of them have reportedly been executed.

CONGO IS FULL OF COLONIAL-ERA BUREAUCRACY, THE TYPE OF FUTILE rubber-stamping that Joseph Conrad captured in Heart of Darkness. To visit even the lowliest government official you must pass through “protocol.” This means entering a windowless cement room on the outskirts of a massive, decayed complex and presenting yourself to sleepy guards with guns at their feet. One guard will record every petty scrap of information about you in a ledger the size of a school-bus windshield. For his trouble, you will hand over enough money “for a Coke,” about 100 (devalued) Congolese francs,or roughly 30 cents.

Such was the procedure as I entered Kabila’s palace on a scorching Thursday to begin my interview. Before heading to Congo, I’d spent a freezing winter day with Kabila’s U.N. ambassador, Ileka Atoki, in his overheated New York office. The ambassador had assured me that Kabila,who was touring Europe at the

time to drum up investors,would happily meet with me to spread the news about his regime. He warned me to be patient,though:“It is Congo,” he said in a crisp French accent (French is the official tongue of central Africa), “and people work on Congo time.” Still, I’d expected that arranging a meeting wouldn’t be much harder than landing an interview with a midwestern CEO.

But it turned out that my meeting with the president wouldn’t take place on the scheduled day.After I complained that I’d come 6,385 miles and that we had a deal, Kabila’s press secretary was sympathetic and promised to call if the president changed his mind. Several other news outfits, including the New York Times and Reuters, had also been denied access. Finally, after days of endless shakedowns and powwows in filthy corridors of power—and just 24 hours before I’m set to leave—Kabila finally agrees to an exclusive talk. It will be just the two of us. The woman from the Times has scurried back to Nairobi; the Reuters guy has already left to catalog some fresh bloodshed.

It’s been a terrible week for Kabila. The city’s newspapers blare dire headlines; Western diplomats say the young leader is losing his grip. It seems that one of his generals has arrested a high-ranking major wanted for his alleged role in Laurent Kabila’s murder; one of the myriad political groups that make up Congo’s government rabidly opposes the arrest and fears imminent execution. Under the guidelines of the cease fire, Kabila must confer with his four vice presidents on all decisions. One of them,Azarias Ruberwa, has threatened to pull out of the government.“This was a clear violation of the peace accords,”

Ruberwa told me six days before I sit down with Kabila. The situation reveals why many question Kabila’s leadership skills. If the president ordered the arrest, then he acted outside the accords, and therefore foolishly. If the arresting general acted on his own, then Kabila has no control over his own army.

“Either way,” says Philomene Omatuku, deputy president of the National Assembly, “it looks bad for him.”

A FEW HOT NIGHTS AFTER MY ORIGINAL APPOINTMENT TO MEET WITH the president, I take a table at the Grand’s bustling tiki bar and watch a stream of French oil executives and model-gorgeous Congolese teens with Gucci bags head upstairs to a disco called L’Atmosphere. I’m listening to the bug zapper toast malaria-ridden mosquitoes when a man with silver hair flags me from a nearby table. His name is François. He’s 56, a diamond miner from Belgium with a wife and two kids, and he is about to die. In five days he will travel home for triple-bypass surgery. As he chain-smokes Marlboro Lights,François asks if I want to buy into his diamond business.The few bucks I have on me won’t cut it. “It’s just as well,” François says, smiling. “The Congolese will rob you. If you are an outsider and you do business in this country, you pay everyone.

The diamonds fall off the truck and disappear, if you see what I mean.”

Corruption, kickbacks, and bribery in Congo exist at a level that would impress any old-school European colonialist. Tax agents in the provinces often keep 70 percent of what they collect. If you’re a diamond exporter, officials typically inflate your prices to collect additional taxes. The nation’s state-run industries suffer from similar skimming. “It has always been this way,” says François, with the wisdom of three decades’ worth of business experience here.

“When Belgium left in 1960, everyone said it would go bankrupt without money from Congo. But the opposite happened.” Before long, François is joined by two beautiful women who speak no English but perfect French. After a few more drinks, he offers me one of them. “You can have a Congolese woman for nothing, because they have nothing,” he says in English as they look around the bar, bored. “But the problem is this one here. I have been living with her for five years. She takes all my money and gives it to her family. She has emptied my bank account!”

CONGO HAS ALWAYS BEEN A NATION OF UNREAL EXTREMES, OF HEAT and chaos, greed and brutality. For much of the 20th century it suffered the rapaciousness of Belgium’s King Leopold II,who cynically dubbed it the Congo Free State, even as Belgium ran the land as a private plantation for 75 years. Once burdened by the cruelty of Big Man rule under the notorious Mobutu, who renamed the country Zaire, Congo’s citizens have virtually no knowledge of democracy. Loyalties are to family first and then to ethnic tribe. François’s offer to me has a precedent: There are still parts of Congo where the village chief may hand over any woman—married or not—to a visiting traveler, no questions asked.

The source of Congo’s pain, ironically, is its vast natural resources. After decades of plunder, the Belgians, under international pressure, bestowed a belated independence in 1960. Ethnic conflicts quickly erupted under Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba.Five years later,Mobutu seized power through two coups, chasing Lumumba’s backers, like Laurent Kabila, into the forest, where they seethed, plotted revenge, and festered into regional despots.

For decades, Mobutu ran his nation as a private bank and playground, with the help of the West, which saw him as a bulwark against Communism. He reportedly channeled some $8 billion from the sale of diamonds, gold, and oil into European bank accounts.Yet the United States,along with France,continued to feed him billions. As Mobutu’s kleptocracy bankrupted the country, Kabila railed from his eastern mountain stronghold, Hewa Bora. While Mobutu pillaged, the dedicated Marxist set up his own fiefdom, smuggling gold and ivory into neighboring Rwanda. There are reports he later supplemented his trade—and boosted his reputation—by kidnapping the occasional Westerner. (His Maoist rhetoric attracted Ché Guevara for six months in the 1960s;Ché left Hewa Bora in disgust over Kabila’s disorganization and because his soldiers, many of whom were little more than boys, relied heavily on magic and mysticism.)

By 1996, the United States and France had tired of propping up Mobutu. He was in terrible health, and his army was in shambles. Kabila’s rebels did a seven-month cakewalk all the way to Kinshasa as their Rwandan and Ugandan allies exacted murderous revenge. As a “military adviser” in his father’s army— he’d intended to be a lawyer—Joseph witnessed at least some of these atrocities, which human-rights advocates have since labeled war crimes.

AN ELDERLY BUTLER SERVES ME INSTANT COFFEE IN POLISHED CHINA as I take in Congo’s presidential offices,with their 1980s-era Wal-Mart Mafia glitz (heavy drapes, leather couches, tons of brass and marble). After an hour’s wait, I am led outside,through a metal detector next to a bush of tropical roses, and directed to sit at a smoked-glass table at the end of a long terrace inside Kabila’s walled compound, which is ringed by young bodyguards with guns.

On the lawn is a giant poster of his father; further below is the turbid green river. Kabila unceremoniously emerges. He is six inches shorter than I am and looks uncertain about where to sit. Suddenly feeling like the host, I gesture to the chair opposite mine. He thanks me for coming, for my interest in his country, for being patient.

A few days earlier, Aubrey Hooks, the U.S. ambassador to Congo, told me that Kabila appears as if he isn’t listening when others speak but that the president is in fact a surprisingly “reflective thinker.” During our 90 minutes together, Kabila indeed seems Buddha-like, blinking slowly at my questions and then answering or evading—with muted grandiloquence.

I ask Kabila if he agrees that the arrest of the major made him look—as his critics continue to claim—weak and ineffectual. He chuckles, clasps his hands between his knees, and looks me in the eye.

“Of course that was the impression,” he begins, enunciating in a crisp Hinduesque British accent (Kabila speaks fluent English, Swahili,and French). “But .. . do you read Sun Tzu, Art of War?” Not recently, I tell him, enjoying the surreal appearance of a Chinese tract that connects an African leader with Paulie Walnuts.

“Well, you should,” Kabila says,and laughs again. “It’s a question of strategy. ‘When you think I’m at my weakest, that’s when I’m really very, very strong.’”

THE RUSSIAN FLIGHT CREW LOOKS DRUNK. I’VE HAD A FEW BEERS myself during the long layover at Uganda’s Entebbe Airport, so that doesn’t concern me. I’m more worried about the red square painted on the rivet-covered side of the hulking U.N.-chartered prop plane. It reads: CUT HERE TO OPEN. It’s a comforting thought: At least we have an exit strategy.

While waiting for my meeting with Kabila, I decided that I had an obligation to visit Bunia, a former smugglers’ paradise 50 miles west of the Ugandan border, because this is where some of the worst fighting in Congo erupts. Bunia holds 4,600 of the more than 10,000 peacekeepers the French-led U.N. mission stations here to quell regular militia violence. Experts told me that if I wanted to see the full extent of the trouble facing the president, I couldn’t just lounge in a bar with shady Belgian traders and their 17-year-old arm candy. I had to go where the U.N.was hunkered down in the streets in sandbagged bunkers, where doped-up kids were taking potshots at their passing Humvees.

So I climb aboard with 20 U.N. peacekeepers, many from Pakistan, who are taking this roundabout route from Kinshasa, and try to keep my beer down. As soon as the plane begins its descent into Bunia’s makeshift airport, I can feel the danger beyond the tarmac. In the bare construction trailer that serves as an arrival terminal, a Swiss commander briefs us on safety procedures: There was a shootout here between U.N. forces and the militia a few nights earlier.

Stay indoors at night. Don’t travel without a car. Five of us pile into his white U.N. Land Rover and bump over the rutted road to town. As we drive past the sea of blue tents that are home to 15,000 of the country’s two million displaced people, the commander points to a bullet-riddled house. Avoid this road, he tells us. “Some of these kids who are fighting don’t know the war’s over,” the helpful U.N. press officer Leo Salmeron tells me later that night at the agency’s fortresslike HQ. “A lot of them are orphans whose only family are militia groups.They have nothing else.”

Salmeron sends me next door to a bar, where French peacekeepers and members of the dozen or so NGOs in town are drinking $3 Primuses and trading war stories. They’re joined by two midwestern public-radio producers, veterans of myriad refugee crises. The lively if disjointed conversation goes like this:

“Remember that awful disco in Sarajevo?”

“Remember those Chechnya kids who got blown up in front of our faces?”

“It’s gonna be hot in Sudan. Liberia, too.”

“I’m thinking of applying. After two years in this place . . .”

That night, I check into one of two motels in Bunia. The place resembles a Nevada motor court except for the barbed wire above the steel gate and a rear patio where the owners watch French-dubbed karate movies all night long. The next morning I flag a ride with one of the informal taxi drivers—boys on motorbikes—along the road lined with U.N. tanks to the camp by the airport. Beside the camp is a small market selling used sneakers and rusty pots. It’s not hard to find the gold dealers. There’s plenty of activity in their huts.

Mpaka, 20, and his friend, Tandi, 18, have been panning out of a river 20 miles north of here. It’s been a good week. The militia fighters haven’t found them.

“They make us dig in the riverbed for two weeks, collecting the sand, and then we screen it through the water,” says Mpaka,who’s painted his dirty fingernails in reds and pinks. He has just sold a gram of gold,worth $15 here; he’s happily pawing a brick of soiled francs. I jokingly ask if he’ll buy beer or flipflops

for his bare feet and am pulled up short by his answer.

“No,” he says earnestly, “I am married. I have to take care of my wife and son.”

The gold buyer is getting angry and wants me to leave.He’s nervous that I’m asking about the militia. He may be a member of one himself.

“Sometimes the soldiers come to our homes at night and force us to pay money,” says Tandi. “The soldiers killed my aunt and uncle. They hacked them up with a machete and shot them.”

Is he worried for his own life? I ask. “No,” he says.“What can I do?”

A few weeks earlier, Atlas Logistique, the French NGO that helps manage the camp, wanted to give the displaced villagers autonomy to run their new homes, to control the water supply and determine the best time to clean the dirt ruts that serve as sewers between their huts. So Atlas held elections. The camp was broken into districts, each of which voted for a chief, who then voted for a governing body and, finally, a president. Since most people here are illiterate, candidates drew symbols that represented their beliefs. There were trees, flowers, birds, stunning sunsets and sunrises. One man I spoke to, a 32-year-old district chief named Jamugisa Mugasa, chose the pyramid on the back of a dollar bill.

“Because it has the eye,” he tells me, “and the eye sees everywhere.”

WHEN LAURENT KABILA REACHED KINSHASA HE DECLARED HIMSELF president. Though he’d promised democracy after unseating the tyrant, Kabila quickly morphed into a Mobutu, using the central bank as his purse and outlawing opposition parties. Fifteen months after he seized power, war broke out yet again. Then six of Congo’s neighbors piled on, radiating chaos throughout central Africa. Congo was soon torn apart. The West, chastened by its tragic failure to respond to the Rwandan genocide and swayed toward the new Rwandan government, maintained a hands-off stance toward its blatant occupation of eastern Congo.

At the time of this latest trouble, 1998, Joseph Kabila was in China for six months of military training. He rushed back and reassumed his role as major general in his father’s army. But the young general’s service was less than stellar. That year Laurent jailed him for socializing with the children of Mobutu loyalists. In December 2000 he fled a battle in the eastern town of Pweto. The Rwandan commander who captured the town delighted in showing a group of journalists Kabila’s escape route. But what really angered his father was Kabila’s abandonment of $3 million in military equipment. Again he was jailed.

Kabila refuses to discuss his military experience but tells me that he was very close to his father, that he was his “right-hand man.” When his father died, his family and his father’s hard-line advisers—many of whom had fought among themselves for succession—elevated him to president. They felt that his youth and last name would endear him to the Congolese and assumed the 28-year old would be a puppet.

But Kabila had other ideas. “I was angry over my father’s death,” he says, his expressionless eyes firm on mine, “but it’s not always good to show your anger, because you show your weakness.” Bent on peace, he began visiting Western capitals, looking to revive a dead-in-the-water 1999 cease-fire agreement signed by all the warring parties. He gave the U.N. an open door to deploy peacekeepers, which had been unthinkable under his father. And then, even more shockingly, he removed many of the hard-liners who had chosen him to lead, overhauled the government, and began to revamp the justice system. He also started courting Western businesses—assuring them that Congo was safe. Kabila’s critics complained that making peace with murderous rebels was a mistake. But Kabila, of course, doesn’t see it that way. “We had more to gain,” he says solemnly, “by bringing these people together instead of continuing to kill our people. What’s the use of having the powers of a president in a country that’s divided in half?”

THE FIRST—AND LAST—TIME CONGO HELD ELECTIONS WAS 1960. SO much of the population was illiterate that votes were often cast by tossing pebbles into plastic bowls containing photos of the candidates. Little has changed since then, and the country, despite the U.N.’s 2005 deadline, still may not be ready for democracy. Aside from the seemingly simple task of passing election laws, Congo has no polling machines and no way to uniformly educate its public about the candidates. And after so much border trouble, with various ethnic groups flooding in for decades, there is debate over who is truly Congolese and who should be allowed to vote.

Nevertheless, there has indeed been economic reform under Kabila. It is moving slowly, but it is moving —nothing to sneeze at in the Hobbesian quagmire that is central Africa. Four years ago inflation soared to 500 percent; today it’s at 4 percent. The international community has pledged $6 billion in assistance. The IMF has approved its restructuring program. The World Bank has offered $200 million, with $85 million earmarked for the national budget. But when you look around Kinshasa’s cratered streets and at the garbage piled high in the gutters, you see how long it will take to fix. And you naturally ask the questions Jean, my driver, asked: Where is my job? My food? My health care? When I ask Kabila, he turns quiet and then offers me an undeniably candid assessment.

“In a situation as bad as ours, the weapon that you will always use is the truth,” he says, as a river bird caws in the distance. “Don’t give people false hope. Tell them exactly what’s going on and what the government is trying to do. I say people should be patient. This a nation emerging from five years of division. Germany was divided for more than 40 years and still has its reunification problems.”

But having put the train on the tracks, as one Congolese energy baron told me, Kabila must also redefine himself—and the role of leadership in his country. After 32 years of Mobutu’s rule, and a tradition of blindly obeying the chief—in the village or the presidential palace—the culture of power in Congo must change as well. “Right now the transition is a little bit adrift,” says Aubrey Hooks, the U.S.ambassador. “Kabila is very quiet and reserved. Those are good qualities for peace talks but maybe not for what’s ahead.”

So far it seems Kabila has played a brilliant game of “politics royale,” as one Western diplomat puts it, defanging hard-liners and keeping his enemies close by bringing former combatants together in the capital, where he can watch them and prevent any sabotage to the nation.Despite the dubious loyalty of his vice presidents, it seems certain he will remain on top in the 2005 elections.

Or at least it did until the last week of March,when dozens of disgruntled soldiers loyal to Mobutu staged an early-morning attack on several military posts, two television stations, and Kabila’s home in what Kinshasa officials described as an attempted coup. Kabila quickly appeared on TV to assure the nation that no one in the transitional government appeared to be involved and portrayed the violence as little more than an ill-conceived plot. But at least one official is less sanguine.

“It’s a very serious warning,” Ambassador Atoki tells me from his New York office a day after the attacks. “If we don’t move quickly to draft a new constitution, and prepare for elections,many things may unravel. We didn’t feel that in Kinshasa until today.”

In a continent whose endless stream of atrocities can crush even the bravest optimist—Sudan will explode in ethnic violence days after I leave Congo—Kabila seems serious about aggressively pursuing colleagues accused of war crimes, even though his own role in such affairs remains murky. He has been adamant that the U.N. intervene. A few weeks before the attempted coup, a truth-and-reconciliation panel discussed how Congolese victims—countless numbers of people raped, mutilated, or hacked to death—might find justice, or at least peace.

“You cannot expect to talk of reconciliation without talking of justice,” Kabila tells me, rising to conclude our meeting as an attendant prepares to whisk him away. “That would be a very big mistake. People should stand up, say ‘We did this, and we are very sorry.’”