'The Fighter' and the Damage Done

MEN’S JOURNAL MAGAZINE

MARCH 2011

Photo by Jeff Riedel

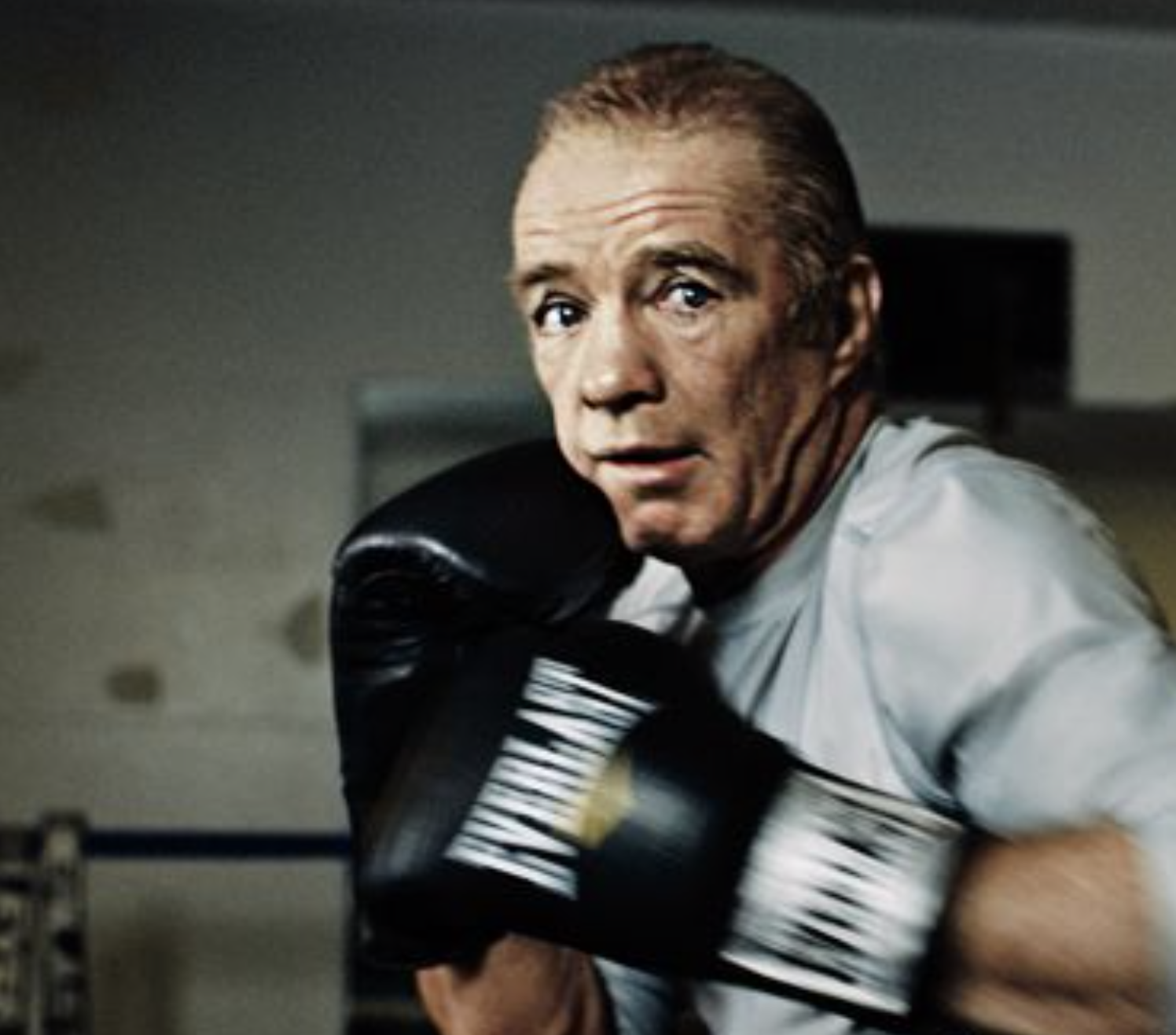

Dicky Eklund, the former boxing champ Christian Bale portrays with twitchy, true-life vigor in ‘The Fighter,’ is pacing his doctor’s office in his hometown of Lowell, Massachusetts. It’s been nine days since his last drink, 10 since his mother nearly died, and three weeks since the movie about his life – and that of his half brother, the boxer Micky Ward – arrived on movie screens across America. Even if he is sometimes embarrassed by the close-up of his messy life, this is his moment. And despite the searing pain in his back, he’s determined to make the most of it.

Wherever he goes around Lowell, strangers tell him – usually with a mixture of awe and apprehension – that they loved every fucked-up minute of the movie version of his life. But right now, Dicky needs something a little stronger than adulation.

“The thing with the pain medicine I’m taking,” he tells his nurse-practitioner calmly, “is that it’s going to be gone so quickly. I take two and I wait six hours, but I suffer. And so next time I take more and now I’m taking four at a time and it works.”

The 53-year-old suffers from herniated disks in his lumbar spine that impinge on his nerves. Surgery will lessen the pain, but that would also put him out of commission. And right now, Dicky Eklund can’t be out of commission. “I gotta fight Danny Bonaduce,” he pleads to the nurse. “I gotta go on a college speaking tour.”

Since The Fighter‘s debut, Dicky has been offering training sessions Opens in New Windowthrough his website at $150 a pop, getting ready to sell custom T-shirts online, and lining up exhibition stunts, like going a few rounds with the former child-star train wreck at a Philadelphia community center, which he’s hoping will net him $1,500. He’d rather not do any of it in the shape he’s in.

“It’s like shooting lightning bolts,” he tells Stacey Gallagher, his nurse-practitioner, a green-eyed beauty Dicky calls his “girlfriend.” He mentions to her that another doctor gave him a larger dosage of the oxycodone than Gallagher had prescribed. “I was crying like a baby and then – whoosh,” he says. “Wow, what a miracle.” He is careful to note what his recent efforts at pain relief have not included: crack, which he has smoked off and on for years. Woven into Dicky’s claim is the threat that if nurse Gallagher doesn’t bend, he may have no choice but to resort to that. “I don’t even drink,” he says. “But I’ll get low one day and back to the old way and then I’ll be dead.” He says he’ll do anything to lessen his back pain. “I’d drink Drano just to make the pain go away,” he says, bobbing on his feet as if standing on hot coals.

Gallagher cautions Dicky not to put off the operation any longer, but he won’t budge. “I can’t do the surgery right now,” Dicky tells her. “Christian [Bale] and Micky say if I get it done now and then come back in six months, everybody forgets about you.” He has a better idea – upping his single-dosage pills from 15 milligrams to 30. “There’s a 30 milligram pill,” Dicky offers hopefully. “I could take a few of those…”

“Sorry,” Gallagher says flatly. “I can’t do that.”

“They go up to 80 milligrams,” he says, whining.

Dicky, as anyone who has sat through ‘The Fighter”s grim crack-house scenes knows, has a well-documented penchant for narcotics. One doctor described him in his medical record as a “pill seeker,” a charge Dicky denies.

“I’m afraid we’re going to get to the point where you’re not going to be able to come off of these easily,” the nurse warns him. “I wanted to discuss you going on a methadone program.” Dicky cuts her short, his tone turning fevered as the promise of stronger pills slips away. “I can’t be seen going into a methadone clinic,” he says. “That’s out of the question. I can just see the headlines. People will be snapping my photo as I go in there.” He tries one last angle, the best card in the Dicky Eklund arsenal of feints and jabs. He slides an arm around Gallagher’s waist, pulls her close, and lays his head on her shoulder. “We’ll spend Valentine’s Day together,” he promises. “You can get rid of that boyfriend.” His arm lingers. “You’re too much, Dicky,” she says. “You’re killing me.”

“The thing with the pain medicine I’m taking,” he tells his nurse-practitioner calmly, “is that it’s going to be gone so quickly. I take two and I wait six hours, but I suffer. And so next time I take more and now I’m taking four at a time and it works.”

By now, the Dicky Eklund story is well known to the millions of moviegoers who’ve seen his family’s drama played out with all its strained loyalties, front-porch melees, and quests for redemption. But what happens after the film version ends is left uncertain. The postscript about Dicky Eklund that comes at the end of The Fighter is strenuously vague: “Dicky maintains his status as a local legend. He trains boxers at his brother’s gym.” The recent real life of the three-time Golden Gloves winner is, in fact, shockingly vivid. Dicky has been arrested more than 66 times, at least several times in the past decade, where the movie of his life leaves off.

In the past four years alone, he has been arrested for cocaine possession and a string of assaults, including a charge of attempted murder. He was questioned in other crimes as well. In May 2006, Dicky was involved in a homicide that took place outside Captain John’s, a bar just down the street from where his life story would be filmed months later. A 29-year-old patron was punched once in the face, hit his head on the pavement, and died. Dicky says the victim was throwing a punch at him when his nephew intervened. In the end, John “Jackie” Morrell, the 25-year-old son of Dicky’s sister Donna, confessed to the beating and served 11 months in prison. “The cops want me for that,” he says. “Cops said I threw the shot. With my record I could have got 25 to life. I didn’t do it. He confessed to it. My nephew, the one that killed the guy, goes, ‘Dicky, they still think it’s you.'”

Dicky had once been a New England welterweight champion, known regionally as the Pride of Lowell. Dicky was a scrappy Irish tough who danced and fidgeted his way through bouts and never suffered a single knockout. His most notable moment in the ring came in 1978, when he knocked down Sugar Ray Leonard Opens in New Windowin a 10-round fight that he ultimately lost by unanimous decision.

For that bout, Dicky was paid $7,500, a pittance compared with the millions his brother Micky made over the course of his career. Their fortunes outside of the ring have differed sharply as well. “He lives out in the Highlands,” Dicky says of his half brother, “where all the fags live.” Theirs is not an easy relationship. “We’re close now,” Micky says. “But, you know, we have to keep each other at arm’s length sometimes. That’s how big families are now and then.”

By the time Dicky’s career ended, in 1985, he’d racked up 19 wins and 10 losses and picked up a fierce crack habit. His spiral into drugs and prison devastated the Eklund family – his mother, Alice; his seven sisters; Micky. Dicky was featured in the 1995 HBO documentary High on Crack Street Opens in New Windowand was later sentenced to 10 to 15 years in prison for, among other things, kidnapping and masked armed robbery. (He and a hooker friend had been luring johns they’d then rob at gunpoint.) It’s only when he got out of jail, after five years, that his younger brother’s fighting career gave him focus. As one of Ward’s trainers, Dicky helped his half brother win the WBU World Championship title in 2000, which is where Hollywood rolls the credits on their story. Micky Ward would go on to bigger and more profitable fights, taking on the late Arturo Gatti in three epic battles Opens in New Windowthat netted him $1 million each. (The first and third fights landed both men in the hospital and each was crowned Ring magazine’s Fight of the Year.) Micky retired in 2003 with a record of 38 wins – 27 by knockout – and 13 losses. Today, he runs a gym in nearby Chelmsford. Dicky had been training boxers at a Cambodian gym in downtown Lowell – a gym that had been renovated to house his training business – but lately he hasn’t been showing up. Now he trains fighters at Micky’s.

Micky’s Corner is less of a boxing gym than a room on the second floor of a Gold’s Gym behind a cluster of condos backed up by a reedy patch near US Route 3, a highway that runs south 30 miles to Boston. On a Tuesday afternoon, a half-dozen moms in Phat Farm sweats and tie-dyes watch soap operas and mall-walk on the treadmills. Just beyond, next to the fire exit, are the stairs that lead to the boxing room, where three bored young guys – including Dicky’s 27-year-old nephew, Sean – sit around a raised boxing ring, waiting for Dicky Eklund. The Pride of Lowell is 40 minutes late. Shortly after 3 pm, Dicky bursts into the room, dancing like an overserved wedding guest, arms in front of him circling, like he’s churning butter, his knees pumping what looks like a jig. “I got CRS,” he tells me, referring to his lateness. I look at him, confused. “Can’t Remember Shit!” He laughs, a cackle of missing teeth and exposed gums that Bale – like every one of Dicky’s charmingly cracked-out tics and motions – has re-created eerily well for the movie. (“Christian is more Dicky than Dicky,” Micky says.) Dicky peels off his sweatpants to reveal a pair of pale grandpa legs.

When he’s boxing, he says, the pain eases up because the muscles loosen their grip on his nerves. He climbs into the ring with Sean and for the next hour or so gains a steady focus, putting his nephew through a series of speed-punching, ducking, and footwork drills so unrelenting it’s easy to see how he pushed his brother to win a world championship and why he is considered by some boxing experts to be an intuitive trainer and an effective motivator.

Amid a steady stream of comedic ball-busting, Dicky catches Sean in a corner and dry-humps him to the beat of “Love Train” blaring over the gym’s speakers. Sean giggles in submission while the peanut gallery ringside erupts in laughter. But just as quickly, Dicky is back to business, showing Sean how to quick-slide back and around, leaving his opponent punching air. “Push! Gimme that slide,” Dicky says, wielding a pair of focus mitts and directing Sean to rabbit-punch the pads. “Gimme that right and up. Show me who’s boss!”Dicky’s fighting style is jumpy and frenetic, more like a dancer than a brawler, but he clearly has killer instinct. In a 1981 fight, Eklund put his opponent, Allen Clarke, in a corner and pounded him relentlessly long after Clarke was clearly knocked out cold but still standing. The local TV announcer called it “brutal at best,” going on to say that Clarke was lucky to be alive that night Opens in New Window. Eklund warms to the memory. “You watch that fight on YouTube,” he crows, “and tell me I don’t know how to do the job.”

Now Dicky is hoping the movie will bring him training gigs that will pay more than the $40 per session he gets from the local hopefuls and gym rats looking to spice up their workout routines. “I got a guy coming out from L.A.,” Dicky says, “paying $150 for a lesson.” Predictably, there’s a website (run by his 36-year-old daughter, Kerry), DickEklund.com Opens in New Window, and a line of T-shirts with some of the Dickyese, as he calls it, immortalized by Bale in the movie. “I’ll hit you right in the cocksucker,” “Hey Quacker!”, his pet name for crack.

“I had a notebook full of Dickyese,” says Bale. “I would take it with me every day to the set, and I had Dicky there in case I needed more. We would talk to each other between takes in Dickyese.”

Outside the gym, Dicky lights a Newport and tells me a story: “Two weeks ago, I was helping this hooker,” he says. “Some kid with a screwdriver was holding her up. I said, ‘This girl works for her money. She ain’t sucking your dick.’ So I popped him. Bam. Out cold. Then she calls me up the next day. ‘Quacker! I’m at the hotel and I got some stuff. I want to thank you.’ But, see, I can’t do that anymore.”

It wasn’t until Mark Wahlberg called to say he wanted to make a movie about him that Micky Ward realized he didn’t own the rights to his life story. Dicky did. Or rather, a production company working on behalf of Dicky did. In a lawsuit filed in August 2003, Ward claimed that Dicky, his half brother and trainer, had tricked him into signing away his life rights – for $1,000. Ward signed the contract while preparing for his third fight against Arturo Gatti and, he said at the time, “I signed it to get Dicky out of my hair.” He claims Dicky told him the movie was about his life, not Micky’s, and that he would play only a small role. Dicky tells me the producers duped him as well. “I never in my life would hurt Micky that way,” he says. The contract promised Micky Ward between $75,000 and $200,000, plus a small percentage of net profits from the film if it was made. Ward settled the suit three months later, under confidential terms, and entered a new agreement with Paramount. Still, it took three more years for Wahlberg to come on board, in October 2006, when Brad Weston, president of production for Paramount Films, called Wahlberg to see if he’d read a script the production house had. It was about Dicky and Micky. Paramount had obtained the rights. Soon, the two fighters were flying to L.A. for meetings.

The Fighter was shot in 33 days in Lowell in 2009. Dicky often worked with Bale on the set – as a boxing coach and authenticity consultant – and he didn’t always like what he saw. “Dicky’s is a fascinating roller coaster of a life,” says Bale. “And he’s having to see all of the lowest points of that life. No one wants that. Everyone wants to see all the golden moments. But that’s not a story. And his life is a wonderful story and, alongside his brother Micky’s, a wonderful story that takes fortitude to be able to see.” Bale has jokingly said he had to keep Dicky from throwing a punch or two at director David O. Russell during filming. “I don’t think he’d have landed one on him,” says Bale. Complicating matters was that the whole town would turn out to watch the Eklund family watching themselves being acted out on the street.

During one scene, in which cops are beating Bale’s character outside a restaurant, Dicky’s real sister Gail came screaming up to the actor-cops. “That’s my brother! Leave my brother alone!” recalls Dicky, laughing. “Russell had to cut filming until we calmed her down.”

While the script was being hammered out, Dicky and Micky moved in with Wahlberg in L.A. so they could coach the two actors in the ring in Wahlberg’s home gym. Bale says that one day Dicky was reading the script and looked up at Bale with rage in his eyes. “He said, ‘I done a lot worse than what you guys are showing,'” Bale recollects. “‘But do you guys have to show my sisters and mother this way?’ He was always more concerned about them than himself.”

When The Fighter premiered in Lowell in December, it seemed as if the entire town – more than a handful of its residents make appearances in it – filed into the Showcase Cinemas to see it. Many more showed up just to watch its stars, and the actors who play them, parade into their afterparty. Dicky had seen the film weeks earlier with Bale, Wahlberg, and Ward at the Paramount lot in Los Angeles. “I hated it,” he says. “But it was what it was.” He complained to Bale and Wahlberg: “Micky looks like a million bucks, and I look like a two-dollar bill.” He was embarrassed. “We got into my truck after the screening and Dicky just said to me, ‘You fucker. You fucker,'” recalls Bale. “‘You’re a fucker, but you nailed it.'” Bale, who had grown close to Dicky during the filming – and still calls him a few times a week – was troubled by Dicky’s reaction, so they set up a public screening for him in New Jersey a few weeks later so that he could see for himself how an actual audience would respond. “I wanted him to watch it without a bunch of people turning to him and saying, ‘What did you think?'” says Bale.

“Afterward, people in the theater were all excited; they stood up clapping,” Dicky says. “Next two times I seen it, including the premiere in Lowell, people went crazy.” Dicky is still embarrassed but also realizes now that Bale’s Oscar-winning portrayal Opens in New Windowactually makes him – not Micky – the star of the film. “That’s what people tell me, anyway,” he says. “But it’s still hard to look at.” Four years ago, Paramount paid Dicky $193,000, in two installments, for his life rights and for participating in the film. He soon blew through it all and is now getting by on what little training he does. At the party after the premiere, Bale posed for dozens of photos with locals – $20 a pop, with all proceeds, about $700, going to the Dicky Eklund fund.

“People think I’m rich from the movie,” he says. “I can go into a bar or into the drug house and get anything I want – thousand dollars’ worth of stuff. But go and try to get 50 bucks a month for your electric bill or gas bill and you can’t get it. But people want me around. ‘Dicky’s here. There’s the guy who played in the movie!'” Bale tells me there’s an essential element to Dicky’s character he felt determined to capture – one that’s easily misplaced amid all the dramatic energy of family squabbles, dysfunction, and criminality. “Dicky is the loyalest guy you’ll ever meet,” says Bale. “And one of the things he was looking for in the movie was: Were we loyal and could he trust us? He’s funny and clever and bloody sharp and full of charm. And he’ll kick your ass into shape. He’s a genetic freak, like the Energizer Bunny. But loyalty is his essence.”

Dicky Eklund lives in a three-bedroom apartment on the first floor of a 19th-century Victorian that’s seen better days. “It’s a ghetto house,” he warns me as we climb the steps. The screen on the front door is framed in wads of duct tape. The entry hall is bare but for two large photo posters: one of a sweaty Dicky hugging his bloody brother in the ring after a fight, and the other a faux fight poster from the movie. Dicky keeps apologizing – for holes in walls, raw Sheetrock with dangling electrical wires, the guts of a doorbell exposed in the kitchen – but it’s otherwise spotless. “Dicky is an obsessive cleaner,” says his girlfriend, Leslie Stephens, a 43-year-old former nurse. (She’s on disability because of a hand injury.) “He’ll come home with $100 worth of groceries,” she says. “And it’s all cleaning supplies.” The couple has lived here for about a year. “Our house before this was nice,” Leslie tells me. “In a nice area. You shoulda seen it.” The new apartment is in a neighborhood known as the Acre Opens in New Window. It’s one of the city’s oldest and most blighted neighborhoods. It’s where Dicky and Micky grew up. The room is decorated in Bob’s Discount Furniture. Scented candles line the mantel above the walled-off fireplace, flanking decorative photo frames that say love and family. Leslie says she and Dicky have been together for 10 years, though he claims it’s more like four. “I used to chase him around when I was 18 and he was 28,” she says. Dicky laughs: “There were thousands of girls chasing me then.” Leslie adds, “He doesn’t remember me.” We are going out to dinner, and she’s laid out Dicky’s clothes, as she does every night. She lays out his pajamas if they’re staying in, which she tries to get him to do as much as she can. “He’s staying in more. He likes to go out once in a while, but he’s finding there’s nothing out there,” she tells me, sounding like a proud mother. “He must be growing up. Some people think I’m too hard on him. They come to the door and I say, ‘Leave him alone.’ He’s not going out because he gets the headlines, and they don’t.”

Their relationship isn’t always harmonious. Two years ago, almost to the day of our visit, Leslie called the Lowell police. “My boyfriend just beat the shit out of me,” she told cops when they arrived. According to the police report, she said Dicky had gone “crazy,” pushing her onto the couch, climbing on top of her and choking her, alternately pinching her nose and covering her mouth with a free hand until she got dizzy. She eventually escaped and called 911. The police charged Dicky with assault with attempt to murder – a charge commonly applied when an alleged assault includes strangulation. Prosecutors later dropped the case after Leslie refused to testify.

The pattern continued last summer. Leslie called the cops and Dicky was arrested, but the prosecution could not go forward because she again refused to testify. (When I ask him about it, he says that Leslie had been chasing him out of the house and tripped while trying to prevent him from leaving. “I said I was going out, and she thought I was going out partying.” He puts his hand to his head and makes a circular motion, the international symbol for “crazy,” and then he laughs. “She thinks every girl in the world is gonna rape me.”) Dicky’s sisters told me that the two are bad for each other. Dicky has had trouble with other women as well.

Three years earlier, at 9 a.m. on a June morning in 2007, cops responded to a report of a man beating a woman in a parking lot. The victim told them that she and Eklund had been on a date the night before and that that morning, after drinking all night, they got into an argument. The fight led to Dicky punching in the driver’s-side window of the minivan she was in and dragging her by the hair before fleeing in a Camry registered to his mother, Alice. The victim recanted her story – this time in a signed affidavit – and according to court records, the case was dropped.

An hour after we were supposed to have left for dinner, Dicky is still talking. He’s excited about the “motivational” speaking engagements Ward has lined up for them, starting at some college in Florida. Micky has been doing these talks for years, and now – prompted, in part, by the agency that handles Micky’s speaking gigs – Dicky will join him. It’s a way to capitalize on interest in the movie and to help Dicky make a little money. “I don’t know if I can deal with him,” Micky confesses. “I tell him, ‘You can’t talk like you’re talking to a bunch of street kids when you’re at a major college.’ It could be a train wreck. Or it could be great. Dicky has a great story to tell.”

Dicky isn’t likely to pretend his sobriety is anything but fragile, a day-to-day affair. “I don’t like when people – whether you’re clean one day or 10 years – are down on people who are partying,” he says, “because you can be back there tonight. One slip, you can be back there. Worry about yourself; you can’t help nobody else.” “Oh honey,” Leslie says, not taking her eyes off the flatscreen TV. “You’re a whole different person.”

“No,” says Eklund, spinning toward her, annoyed. “I’m talking. I’m just telling some stuff. You can’t go to those speaking classes I’m gonna do at colleges and say, ‘Honey, you’re a different person.’ Imagine her,” he says to me, “when I’m speaking? ‘Miss, you want to be a part of this?’ I get so into it and tell the truth. I don’t want to glorify what I’ve done.” He shuffles into the bedroom, where Micky’s boxing gloves hang above the queen-size bed’s headboard. Eklund comes back into the room, a brown polo shirt tucked into his slim-fit Levi’s but still wearing his Michael Jordan shower sandals, over a pair of white socks. “Not bad for 22, huh?” he says.

At the restaurant, a Mexican-Irish mash-up called Garcia Brogan’s, the bartender greets Dicky with a hearty handshake and a loud “Heineken?” Leslie shakes her head and shoots Dicky a look. Dicky winks to me and orders two Cokes. Leslie spends the dinner latched onto his arm. Everywhere Eklund goes these days, people stop him – or else stare and whisper. If he manages to catch them staring, he’ll go out of his way to engage them. After dinner, he sees a table of twentysomethings glancing our way. He dance-boxes his way over and tells them that I’m in town writing a story about him. One young blonde asks, “Did you really jump out of a window all the time?” Eklund looks only slightly put off. “Yeah, but probably just once,” he jokes. “It hurt, too.”

The next day Dicky calls me, crying. “My mother died. This is awful.” At some point during the night, Alice Ward’s heart stopped beating, and before the doctors somehow revived her, the family got word that she’d died. Once they learned that she’d survived and had been put on a ventilator, they piled into the car to say goodbye while they still had the chance.

Dicky’s Camry has an expired inspection sticker and four bald tires and is leaking oil, so I offer to drive him, Leslie, and a carful of grieving, anguished sisters an hour south to Boston. Micky gets the word at his hotel in New York and arranges to fly in on an 11 pm flight. “Alice is the rock in that family,” says Mickey O’Keefe, the police sergeant who trained Ward, and in the movie version, clashes with Dicky over his drug use and mismanagement. “If she ends up going, they all go.”

But Alice goes nowhere. In the next few days, she ends up making the type of miraculous recovery that The Fighter would probably script for her. The next morning, local talk radio and people all around town are talking about how Alice Ward came back from the dead.

Like Alice, the Eklund sisters hated the movie versions of themselves – in part because they were made to look unattractive. “Those women were ugly,” says 47-year-old Alice Eklund, who, like her sisters, received $500 for participating in the film. “I never had hair like that. And Cathy – Cathy was a poster girl in the 1980s when she was waiting tables in Florida.”

The last time I drop Dicky off at his house, a weak winter sun is setting over Lowell, and he is telling me he needs an agent. It’s likely that he’ll make more money from the film if its success continues – he says he and Micky are splitting 3 percent of the film’s back end – but that could take a year or two, and he’s looking for something more immediate.

“I need someone to get me an ad. That would be awesome. Me jumping out of a window for that trash-bag company, the real tough one, Hefty. I go inside it, and it still holds me.” Jokingly, he provides his own voice-over: “‘Yeah, yeah. There he goes again!'”

Dicky takes 20 minutes to say goodbye, as if he knows that his close-up is coming to an end. “They want me to train Mark Wahlberg for a fight with Will Smith!” he shouts at me, suddenly afflicted with celebrity-induced Tourette’s. Then he says, “Hang on,” and runs up the stairs to his apartment. For a moment, the briefest second or two, it’s quiet. But then he’s back, banging the front door open and bounding down the steps. He’s holding a soiled pair of boxing shoes.

“Ten years ago, I got these shoes,” he says, breathless and grinning, more triumphant than I’ve ever seen him. “These are Micky’s world-champ shoes. He threw them away on a beach in Florida. I got them out of the trash. Now I can put them on eBay, but I gotta get Micky. He needs to find time to sign them for me.”