What Ever Happened to AIDS and Straight Men?

DETAILS MAGAZINE

MARCH 2004

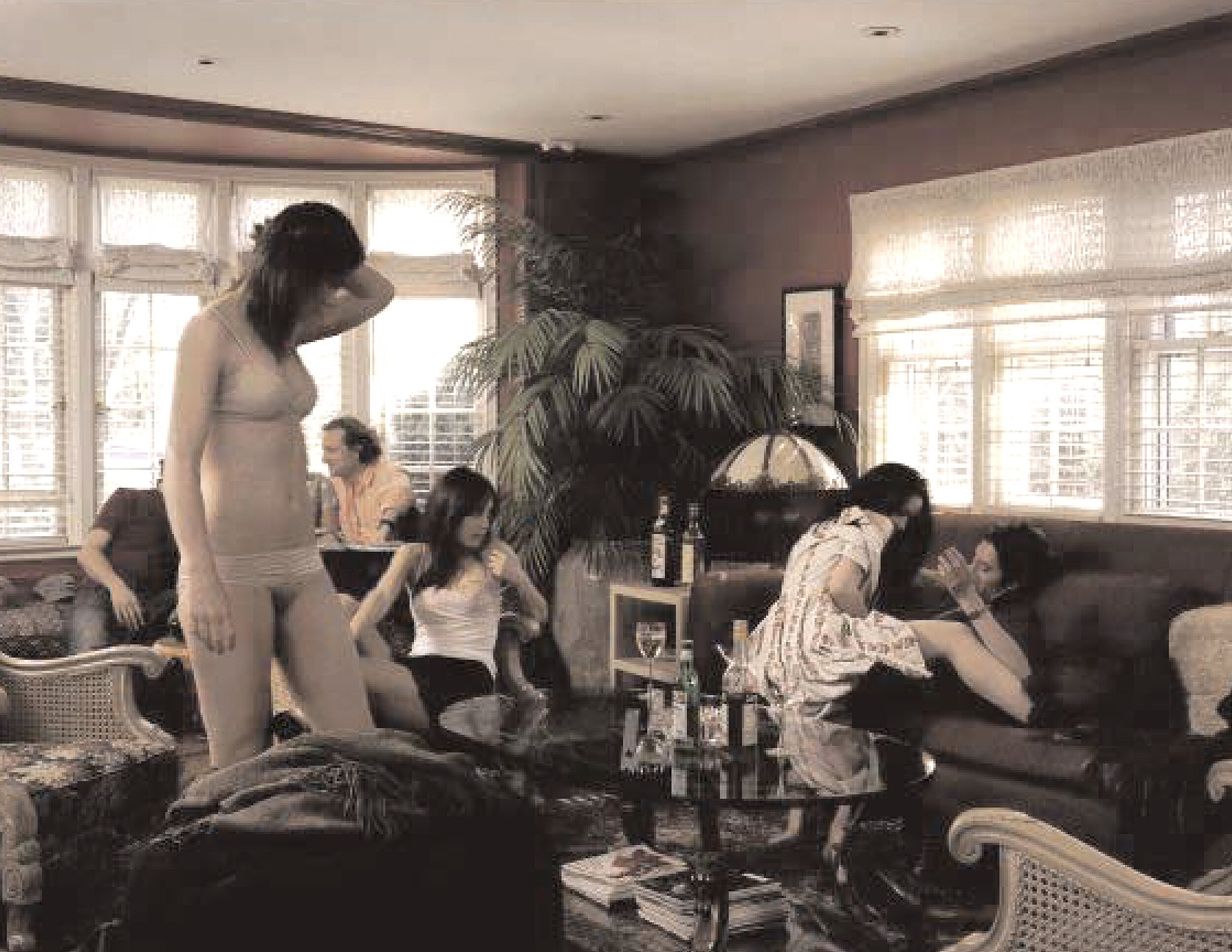

Photo by Collier Schorr

In 1987, America was obsessed with sex. On the radio the average high school rocker heard the command to “Push It” and eagerly obliged. On Friday nights he put on acid-washed jeans and took his date to see Glenn Close boil rabbit. He received stud lessons from a beer-guzzling, model-nailing pooch named Spuds Mackenzie. He channel-surfed in parachute pants and saw Jessica Hahn bring televangelist Jim Bakker to his knees.In between, he found TV’s first ever condom ads. Yes, sir, sex was on his mind. And it was about to turn deadly.

That fall, federal health officials sounded a terrifying alarm: AIDS could kill anyone. For six years we had known that the disease was stalking America’s gay men and intravenous-drug users. It deposited purple blotches on their skin, sent their minds into spirals of dementia, reduced their bodies to withered skeletons. Our high-schooler had heard about it, but he didn’t give it much thought. Like most of America, he vaguely worried that he might catch it from a toilet seat, a sneeze,or a handshake. But it didn’t truly . . . concern him.

Until the panic landed with a thump at newsstands. Stacks of U.S. News & World Report heralded “the dawn of fear,” telling him “The disease of them suddenly is the disease of us.” AIDS, it seemed, was spreading through the heterosexual population—through straight sex!—at a fearsome rate that health experts likened to the Black Plague. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop called it “the biggest threat to health this nation has ever faced.”

Suddenly, wherever our kid turned—MTV, Time—he saw a parade of the walking dead, people who looked and talked like him, grimly recounting one night-stand horror stories. The message: Whether you’re a Berkeley co-ed or a Portland plumber, plain old vanilla intercourse can kill you. And in case he still didn’t get it, from daytime TV came a voice so grave, so full of maternal concern, it stopped him dead in his Reeboks. “AIDS has both sexes running scared,” Oprah Winfrey said. “Research studies now project that one in five—listen to me, hard to believe—one in five heterosexuals could be dead from AIDS at the end of the next three years. . . . Believe me.”

The idea was staggering. Nearly 44 million people—dead in less time than it takes to finish college. AIDS anxiety suddenly gripped the country. Our young guy recalled last Saturday’s bar pick-up, a buddy’s too-easy sister, even his new girlfriend. How well did he know her? Some mornings he saw, or thought he saw, a red rash spreading across his flesh (hadn’t it just been a vigorous romp?) and bolted to the nearest clinic for a blood test, joining a brotherhood that doctors called “the worried well.” Sex was no longer just a game; it was Russian roulette.

SINCE DOCTORS FIRST REPORTED THE OUTBREAK OF A MYSTERIOUS NEW DISEASE in 1981, an estimated 900,000 Americans have been diagnosed with AIDS. Nearly half of them were men who’d had sex with other men,27 percent were IV-drug users, and another 7 percent were both. But the politically incorrect truth is rarely spoken out loud: The dreaded heterosexual epidemic never happened. Straight men and women make up 90 percent of the population, but they account for only 15 percent of non-childhood AIDS cases. Only 6 percent of men with AIDS, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says, contracted the virus from straight sex. And even that figure doesn’t hold up to a closer look. Several studies now suggest that most men who claim they got the virus this way are lying. They got it from sex with other men or sharing needles with addicts. Those studies also show that many women listed in the straight-sex category are either IV-drug users themselves or have likely contracted AIDS from sex with an IV-drug user.

Health officials have known these things for years.A growing pile of federally funded reports on HIV transmission, published over the past decade and available to anyone who has time to read them, shows that men almost never get HIV from women. In fact, according to a 1998 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a disease-free man who has an unprotected one-nighter with a drug-free woman stands a one–in–5 million chance of getting HIV. If he wears a condom,it’s one in 50 million. He’s more likely to be struck by lightning (one in 700,000).

“Female-to-male transmission is very inefficient,” says Dr.Nancy Padian, a professor in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, and the author of a 1996 10-year study of HIV-infected heterosexual couples, the nation’s longest and largest. She points out that “it’s two to three times easier for men to infect women.” But even so, if there are no other risk factors involved,the rate at which an infected man will transmit the virus to a woman is one in 1,100 sex acts.

Today it’s clear that the AIDS epidemic in the United States peaked in 1993—when 106,000 new cases turned up. Then it began a slow decline and has now leveled off to 40,000 new cases a year. Thanks to powerful anti-retroviral drugs that allow HIV-infected people to live longer, AIDS deaths have plummeted 14 percent since 1998, falling in 2002 to a new low of 16,371. Clearly, a single death from this awful illness is one too many. But AIDS is not killing Americans at the levels of cancer (554,000 deaths in 2001), diabetes (71,000), or Alzheimer’s (54,000). In fact, the CDC has not put the disease on its list of the top 15 killers since 1998. America may be winning the war on AIDS,but not without collateral damage.

After two decades, we are still overwhelmed with misinformation and misconceptions about how the virus spreads. Straight men are still haunted by the notion that old-fashioned sex can be lethal. Among the biggest fear factors, some AIDS educators say, is shoddy federal health data. The CDC statistics are only as good as the local health departments that gather them. But many of those departments don’t have the time or resources for “surveillance” staff to investigate every person’s claim of how they contracted the virus. If a man wants to lie about having had sex with other men, he can, and that makes it look like more people get AIDS from straight sex than really do. By re-interviewing victims, their doctors, and their families, Chicago health officials found in 1997 that in 85 percent of the cases the city had blamed on heterosexual transmission, other risk factors were present. This phenomenon became a source of black humor at New York City’s overworked health department in the late eighties. “What do you call a man who got HIV from his girlfriend?” the joke went. “A liar.”

The truth is out there, but it’s not reaching people who have been needlessly scared—the result, some critics charge, of a conspiracy of silence. “It’s not in anybody’s interest to clear this up,” says Joseph Sonnabend, a physician who treated some of New York City’s first AIDS cases. Sonnabend helped found what later became the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR), but he quit the group in the mid-eighties when it claimed—falsely, he believed—that a heterosexual epidemic could be coming.“Gay men don’t want it fixed because they’ll be blamed again for the disease,” Sonnabend says. “Charities like amfAR don’t want it fixed because they’ll lose their funding. And ‘straight’ men with HIV certainly don’t want it fixed because then everybody will know they’ve been having sex with men. Those are the ones who will scream bloody murder if you print all this stuff. You’re outing the poor bastards.”

ANY OVERHAUL IN AMERICA’S AIDS POLICIES HAS TO BEGIN WITH AN OVERHAUL of public perception—away from the anyone-can-get-AIDS mentality. That means looking at the cultural forces that originally shaped that perception and continue to do so today. Many scientists now say that the first major public awareness program, 1987’s America Responds to AIDS campaign, was not only largely wasted on mainstream America but deadly to those most at risk, drawing precious funds from the very people AIDS was attacking: gays, bisexuals, drug addicts, and the poor.

Certainly the horizons of the AIDS epidemic were less clear in 1987.“ With diseases like this you’re working with a moving target,” says Walter Dowdle, who helped start the CDC’s anti-AIDS office. “We knew the groups hardest hit were gay men and drug addicts. But we didn’t have a lot of information about heterosexual spread.”

Nevertheless, by 1987 the CDC knew that vaginal intercourse was an extremely inefficient way of transmitting the virus. The agency had already produced research that showed the widespread fears of contagion were exaggerated. Less than two months before it launched its AIDS campaign, theCDC’s epidemiology chief, Harold Jaffe, publicly criticized the everyone-gets-AIDS message, noting the risk to straight America was “very small.”

“People would talk about the hypothetical housewife in Des Moines,” says Jaffe, now the director of the CDC’s AIDS-prevention program. “Was she at risk? The answer was ‘not really,’ unless her husband happened to be a drug user or bisexual.”

In trying to address groups at risk—gay men and drug addicts—the CDC’s Dowdle had already run into political and cultural roadblocks. Broadcasters refused to carry announcements advocating condom use. Ronald Reagan remained infamously silent on AIDS almost until the end of his presidency, and moral objections led his White House to quash the publication of a 1986 brochure prepared by the CDC that touted condoms. “We were getting virtually nowhere with the Reagan administration,” Dowdle says. “They paid no attention to it at all.”

Congress, though, had become increasingly alarmed by the CDC’s reports—loudly disseminated by gay activists and charity groups like amfAR—that AIDS was killing off straight Americans. In 1987, Congress ordered the CDC to send out a nationwide mailing to educate Americans about the dangers of AIDS.

Dowdle, who was put in charge of this mission, knew that mainstream America cared little for the plight of drug addicts, prostitutes, and homosexuals. William F.Buckley Jr. had suggested that anyone with HIV be tattooed to protect the healthy. Liberace died of the disease without ever admitting he had it. When Americans were asked by Gallup pollsters if AIDS was God’s punishment for immoral behavior, 43 percent of respondents said yes.

There was only one way to make all Americans concerned about AIDS: put out the word that the disease was an equal-opportunity killer, one that could get your best friend or your mom. Otherwise, straight America would never support the kind of funding desperately needed for research and care. “Only by democratizing the epidemic,” says Dr. Ronald Bayer, a professor of public health at Columbia University, “by saying we’re all equally at risk, would anyone pay attention.”

TO DO THIS, THE CDC NEEDED PROFESSIONAL HELP. AFTER PUTTING A $27 million campaign out to bid, it hired one of the nation’s largest ad agencies, Ogilvy & Mather, and specifically the services of a bright 32-year-old ad man named Steve Rabin, who headed the agency’s health unit in Washington,D.C. Rabin, an openly gay man who had seen friends die of AIDS, held 20 focus groups around the country that August and found that nearly all Americans— straight and gay—thought of AIDS as someone else’s problem. He knew, and his CDC bosses agreed, that they had to underscore the universality of AIDS to make it a public-health priority.

That fall, Rabin shot a series of 38 TV spots, many of which featured men and women with AIDS. They were not identified as gay or as IV-drug users, and the ads addressed their high-risk activities only in veiled ways. During the filming, one young man,the son of a Baptist minister, looked at the camera and said, “If I can get AIDS, anyone can.” The line was an unscripted surprise, and it became the unofficial slogan for the campaign—the TV spots, along with eight radio announcements and six print ads, all of which made a personal, heartfelt appeal to Americans to talk to their families about AIDS. What the CDC knew, but kept from the public, was that the young man was gay. Instead he was presented as an equal-opportunity victim—a preacher’s son!—of the burgeoning pandemic.

In July 1988, the CDC mailed its “Understanding AIDS” brochure to 126 million American households. Coming from C. Everett Koop’s desk, it finally used the frank language activists had sought, talking about anal sex and discussing the use of condoms and lubricants (even warning against items like Crisco because they break down the latex in condoms).

But despite the plain talk, the brochure still blurred the line between mainstream Americans and those who were at high risk. A middle-aged blonde stared out from one page, telling those Des Moines housewives and Dallas freshmen that “AIDS is not a ‘we’ ‘they’ disease, it’s an ‘us’ disease.” What the brochure didn’t mention was that she was an IV-drug user.

The media heard the alarm and dispatched its legions of camera crews and producers. The three major networks ran graphic coverage of the brochures on their nightly newscasts. “We jokingly called it the anal-sex triple crown,” Rabin says, noting it was the first time that those words had been uttered on national TV. The campaign, along with the media coverage, transformed AIDS from “the gay cancer” into a mainstream obsession.

The vision of a heterosexual plague fit nicely with the goals of two other camps, which agreed on almost nothing else: the gay left, which saw it as the only way to make straight America pay attention, and the Christian right, which found in it a powerful weapon to beat back the sexual revolution. If sex crazed Americans couldn’t be shamed into chastity and monogamy, by God, they could be scared into it. This was a message that a nation hungover from the binges of the sixties and seventies was ready to hear.

“I used to say we were like the body of a bird being beaten to death by the left and right wing,” says James Currin, who was head of the CDC’s AIDS program at the time and is now dean of Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health. “The gay community had its civil-rights agenda and people on the right had a political, traditional-values agenda.” As a result, in the public mind AIDS was now swiftly spreading through the entire population.

A DECADE AND A HALF HAS PASSED, BUT THAT BELIEF HASN’T GONE away. Indeed, it has been pushed by health experts urging condom use to protect against all STDs, by feminists seeking to make men more responsible for their sexual behavior, by TV news shows looking for scare ratings, and by a national hunger for innocent victims. How could anyone imagine that God was punishing Ryan White, the 13-year-old who contracted HIV from a tainted blood-clotting agent in 1984 and died in 1990? White’s specter continues to haunt the AIDS landscape. Though HIV was virtually wiped out from the nation’s blood supply by 1985, the Ryan White National Youth Conference attracts more than 600 people each year to such uncontroversial workshops as HIV prevention through the arts.

Heterosexual AIDS even acquired a celebrity spokesman in 1991, when Magic Johnson announced he had contracted HIV through promiscuous sex with women. Activists trotted him out to warn America of the AIDS bogeyman lurking at the foot of the bed, a role he still serves today. (Johnson did not respond to several interview requests.) Meanwhile, red ribbons flutter down red carpets. The paparazzi regularly shoot Liz Taylor and Liz Hurley, Macy Gray and Tim Robbins heading into the latest amfAR fund-raiser in Cannes to net another million at events sponsored by Volkswagen and De Beers.

But more than any other force, television news, that bastion of American skepticism and objectivity, has fanned the heterosexual panic from the start. One 1992 study found that the AIDS victims shown on the nightly news were almost never gay men or IV-drug users, despite the overwhelmingly greater incidence of the disease in those groups. The disparity, says Michael Fumento, a conservative science writer and former AIDS analyst for the U.S.Commission on Civil Rights, is the fault of journalistic “crusaders,” reporters who peddle sentiment rather than skepticism, cherry-picking victims who look like the viewers. Media outlets boost ratings by keeping us glued to the tube out of terror—and along the way they reinforce the idea that we are all equally at risk.

“It’s the same thing with SARS hysteria,” says Fumento, a debunking specialist who wrote the controversial 1990 book The Myth of Heterosexual AIDS. “Scientists said over a million people could die. CNN claimed it could overwhelm the U.S.hospital system. Not a single American died. The media likes a good story and it doesn’t understand its own limitations. It doesn’t look under the rug.”

FOR ALL ITS LETHAL IMPACT, HIV IS A WEAK VIRUS. LEFT AT ROOM TEMPERATURE FOR a week, it has only a 10 percent chance of survival. Simple cleaners, such as dish soap, can kill it. Unlike herpes and gonorrhea, which can be contracted through genital contact, HIV is transmitted when blood or semen makes its way into tears in mucus membranes or the skin. STDs that cause open sores help HIV enter the body; such concurrent infections are now understood to be crucial in spreading AIDS.

AIDS works like this: HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus, attaches itself to lymphocytes, including T cells, which are responsible for calling other immune cells into action during an infection. The virus then starts incubating inside the host cell, avoiding detection by the patrolling antibodies. During this time, which can last a decade, the virus is dormant but can be transferred to other people through these infected T4 cells.

The question of what triggers an HIV infection to become AIDS is controversial. What is known is that at some point, the virus replicates by taking over the T4 cells, doubling its numbers every 12 hours. Eventually, such work in the service of its enemy exhausts the T4 cell and it dies like an overworked motor. With its T cells devastated, the immune system breaks down, leaving the body vulnerable to the opportunistic cancers and infections that typify AIDS. One such cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma, ravages such internal organs as the lymph nodes, brain, lungs, and digestive tract.

But if HIV can’t reach the lymphocytes, there’s no infection. This is why it’s so hard to contract the virus through old-fashioned vaginal sex. The vagina is a rugged structure, built to withstand everything from a thrusting penis to the passage of a baby’s head during childbirth. Its walls are muscular, covered by a thick layer of epithelial cells that resist tearing and that secrete a lubricating mucus that contains enzymes for fighting off bacteria. Its blood vessels run well below the surface, barring HIV from direct contact with the blood, and thus its lymphocytes.

“The vagina is an organ that is essentially designed to prevent abrasion,” says Robert Root-Bernstein, a professor of physiology at Michigan State University and recipient of a MacArthur “genius” fellowship. “The blood vessels are buried quite deep,so there are no lymph nodes present. So it’s very difficult to get anything vaginally into the blood.”

The rectum, on the other hand, offers almost no protection. It is lined with extremely thin tissue, no thicker than a lambskin condom, and can easily tear. It is part of the lower intestine,which has evolved to perform one major task—uptake nutrients and water from your bowels into your circulatory system—and so it is entwined with capillaries. To keep out the bacteria that thrive in the colon, half of your immune system surrounds your gut in the form of lymph nodes whose sole job is to monitor the water and nutrients re-entering the body.

The rectum has no mucus-secreting cells to help ease the passage of a penis. The subsequent tearing in the cell walls (which lubricants do little to prevent) offers HIV-carrying ejaculate easy access to lymphocytes that cluster just beneath the surface. From there, HIV enters the bloodstream. Dildos, sometimes used before such penetration, do further damage and increase the likelihood of transmission, as do hemorrhoids. A constant hazard of anal sex, hemorrhoids can rupture and bleed, providing the virus with another gateway to the bloodstream. Semen also has enzymes that help it bore through these cell walls, even in the absence of tearing. (Anal intercourse is far less risky for the active partner.)

Interestingly, for healthy men and women oral sex carries practically no risk of infection. Enzymes in saliva attack and deactivate many types of bacteria and viruses. Even those infectious agents that pass this first line of defense are typically destroyed by stomach acids. When semen is swallowed, those gastric juices reduce it to little more than its chemical components, and it largely gets digested as simple protein.

In all three types of sexual activity—vaginal, anal, oral—things get more complicated when other sexually transmitted diseases are present. Those that cause open sores—syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes—increase the chances of both contracting and spreading HIV. If there’s a syphilitic sore on the penis, an army of blood vessels grow around it to bring lymphocytes to the area and eliminate the infection. Not only does HIV get an open door to stroll right in, it also gets an inviting welcome from the lymphocytes,which it clings to like a grateful party crasher.

A healthy man or woman with no STDs and few activated T cells is highly unlikely to contract HIV even if exposed to it through oral or vaginal intercourse. (Of course, anal sex can be just as deadly for a woman as it is for a gay man.) Without activated Tcells to invade, the virus will normally die. “You need these diseases in order to transmit HIV vaginally,” says Donald Capra, an immunologist at Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, who was among the first to publicly question the exaggerated heterosexual HIV figures.

“To the extent that American men have STDs, they also have access to health care. So it’s extraordinarily rare for them to have untreated venereal diseases. A woman with herpes gets Valtrex. A guy with gonorrhea gets penicillin. While there is certainly the young lady who meets a guy, has sex and gets AIDS, and makes the front pages of the newspaper, that’s an exceedingly rare event.”

BECAUSE HIV IS SO HARD TO TRANSMIT, IT HASN’T SPREAD WITH THE BLACK Plague ferocity predicted by Oprah and others in the eighties.The news, however, isn’t good for everyone. Among those who were always at highest risk for infection—gay men, bisexuals, IV-drug users, and their sex partners—AIDS is making a stealthy comeback. A large part of the blame falls on the misguided notion that AIDS is now a “manageable” disease, thanks to powerful drug cocktails that stave off its progression and steroids that make victims appear healthy. (Have you seen Magic Johnson lately?) But an equal part can be pinned directly on all the fear-mongering about heterosexual AIDS. By emphasizing the universality of AIDS—a message fueled by government warnings, celebrity crusaders, and a crisis-craving media—and paying for awareness programs at wealthy college campuses, the country has diverted precious funds from those who need them most. The Bush administration, experts charge, will only hurt matters if it succeeds in increasing the $100 million already spent on abstinence-only sex education. This program, favored in Bush’s home state of Texas, bans discussion of the dangers of specific sex acts and the effectiveness of condoms.

In parts of the Third World, AIDS has, in fact, exploded among heterosexuals. But it has taken hold only in some regions, and among people whose immune systems are already crippled. For instance, the African epidemic is largely confined to the sub-Sahara, where malnutrition, poor health care, and such diseases as malaria and tuberculosis are rampant. In addition, because of their country’s history of apartheid, many South Africans live and labor in squalid camps hundreds of miles from their homes. There, men with untreated STDs will often have sex with HIV-infected prostitutes, contract the virus themselves, and bring it home to their wives, who, when they get pregnant, pass it along to their children. (Rural China, where similar conditions exist, is also suffering.)

Oprah and Bono have lured TV crews to blighted African villages where the heterosexual epidemic is real. Viewers at home are left with the impression that AIDS—always the equal-opportunity killer—could yet make its way into their own bed if they’re not careful.

HIV has indeed crept into American bedrooms, but only those within pockets of poverty, malnutrition, and poor health care. It has become “ghettoized,” and is spreading fastest among the urban poor, particularly among black and Hispanic men (some of them hiding their bisexuality) and black women. The CDC duly reports these facts, but in media coverage the behaviors that put people at risk are glossed over.

Many of the new cases involving black women are simply blamed on heterosexual contact. But it turns out that a number of these infected women have resorted to prostitution to make ends meet. That means they are having unprotected sex, often anal sex, with needle-sharing drug users, and are likely using drugs themselves. But when the New York Times tells us in a front-page story on July 3, 2001, that HIV is taking a toll on rural black women via heterosexual sex,we have to wait until the 36th paragraph to learn that they’re also turning tricks.

“These are not women who stand on a street corner—they go out when they need drugs,” says Root Bernstein, who wrote the 1999 book Rethinking AIDS: he Tragic Cost of Premature Consensus. “They’ll go to a crack house and basically bend over and let anybody do whatever they want for two hours. And the men who are having sex with them will have anal sex because they can do it there and they can’t get it elsewhere, so why not? And when you’re high you don’t care, either. So now we have behaviors that maybe they don’t want to admit to.”

Not only are such behaviors hidden from mainstream America, but the disease itself is beginning to disappear into these crack houses and poverty shacks, just as a 1993 National Research Council report predicted. At the time, the NRC said that the United States would remain largely untouched by AIDS, while those most affected would continue to be “socially invisible” and “beyond ...the attention of the majority population.” That warning “provoked howls of protest,” says Ronald Bayer, the Columbia professor,who sat on the NRC panel that wrote the report. “People said we’d have blood on our hands.” Critics charged that the NRC’s message would cause the government to “neglect the places where AIDS might occur,” Bayer says. In fact,the opposite has happened: The places that have been neglected are precisely those that have been most devastated.

The CDC, acknowledging that prevention efforts have stalled, announced last year that it would focus more money and energy on people already carrying HIV—in effect, shifting to them the burden of stopping the virus’s spread. By diverting $42 million in funding, the move threatens to dismantle, or at least cut the budgets of, 211 community-based groups, most of which serve at-risk minority communities. Among programs that would be affected are workshops that target urban teens, those that teach safe sex in San Francisco’s Mission district, and a counseling program for poor black women in Baltimore, where syphilis rates are skyrocketing. Critics say the move is a dangerous shift away from proven prevention methods; one black AIDS activist said the policy was “insane and, I feel, genocidal.”

“The CDC’s message is to get tested and know your status,” says Dr. Judy Auerbach, amfAR’s vice president for public policy. "But that message is not focused explicitly on the traditional at-risk groups. It’s much more generic, and so you could argue that it’s not reaching the people it needs to.”

To this day, anyone who talks honestly about the true risks of HIV among heterosexuals is asking for the same attacks the NRC report ignited. The most vocal opponents are often those with political agendas or those with the most to lose. “The right-wingers like the heterosexual message because it’s pro-family and warns against extramarital affairs,” says Michelle Cochrane, a visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of When AIDS Began, a recent book that examines some early scientific and cultural misunderstandings of the disease. “Gay men like it because it keeps people aware and keeps funding coming in. And the feminists like it because it gets condoms on the guys and forces them to take greater sexual responsibility.”

It is true that AIDS does not discriminate: Anyone can get it. But not everyone is at equal risk. AIDS is an opportunistic disease in every sense. Not only does it attack the human body at its weakest points; it infects the social body in the same way. AIDS hits hardest where social institutions, such as health-care facilities and drug-treatment programs, are most scarce—among the poor and disenfranchised. As the disease continues to kill Americans, it will not cut across class,racial,or ethnic lines. Instead it will target those who, as the NRC report noted, “have little economic, political, and social power.” This will be the ultimate cost of an AIDS policy that emphasizes moral instruction and abstinence over accurate education about the real risks.

“If you want to stop heterosexual transmission, you focus on poor ghetto communities because that’s where it is, among the drug users,” Bayer says. “You’re not going to stop AIDS by spending money where it’s nonexistent.”

Increasing numbers of researchers say that thousands of lives could be saved each year by spending more on AIDS prevention among at-risk groups: reminding gay men to avoid unprotected anal sex, persuading drug addicts to use clean needles, and teaching prostitutes to insist on condoms. In 1996, James G.Kahn, an epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, brought out a statistical model showing that by spending just $1 million among these high-risk groups over five years, the United States would avert 150 new infections. Targeting low-risk groups would prevent three.

“The public dollar is limited,” Bayer says. “Obviously, if you spend more in ghetto communities, you have less to spend in Scarsdale, New York. And it may be that someone in Scarsdale doesn’t get the message. But there’s a better likelihood that you will have a greater impact if you focus on where the epidemic is. It seems to me that the ethics of public health require you to take care and to protect the greatest number of people. Not scare the hell out of everyone.”