After Prison, No After Hours

THE NEW YORK TIMES

MAY 14, 2014

Photo by Damon Winter

At 10:50 a.m. on Monday of last week, outside the Mid-State Correctional Facility in Marcy, N.Y., which looked like an Ivy League school ringed in concertina wire, Michael Alig emerged from a white prison van.

Mr. Alig, 48, wore a blue button-down shirt tucked into blousy pants and a pair of kitchen-stained prison shoes. His face was thick with middle age, his hair thinning and matted down with pomade. He carried a duffel-size plastic bag filled with diary entries, prison reports and “love letters from other inmates,” he said.

For the first time in 17 years, since he pleaded guilty to killing Andre Melendez — a fellow club kid known as Angel — in a heroin-soaked stupor in 1996, cutting up the body and tossing it into the Hudson River, Mr. Alig walked as a free man.

But he had little time to savor the moment. A 15-person party van filled with friends and supporters, including three guys with dyed and spiky hair who had been sipping Red Bull and vodka all morning, wanted to glitter-bomb him. “We were going to bring a Fisher-Price plastic hammer,” said a guy with a face tattoo, a reference to the hammer used to attack Mr. Melendez.

Mr. Alig barely recognized his old crew and looked overwhelmed. His friend and publicist, Esther Haynes, a former deputy editor at Jane magazine, bundled him into the van. They barely made it across the street when prison guards swarmed in. Two video crews were capturing the scene, and the guards had earlier instructed the cameramen not to shoot on prison grounds. They were now in a standoff.

While the guards radioed their bosses for orders, Mr. Alig played with an iPhone, the first one he had ever held in his hands. “Should I tweet that I’m being rearrested?” he said. “Maybe we’ll have a high-speed chase.”

It would have been an apt return for this self-described “former king of the Club Kids” as he seeks a second act. Did Mr. Alig find redemption and God in prison? Not exactly. In the months leading up to his release, Mr. Alig had been plotting his return to the New York scene, with plans to create a series of reality TV shows, write a memoir and blogs, mount an art exhibition and, of course, hold a few parties — all by trading on his notoriety.

With the help of Ms. Haynes, Mr. Alig has been keeping the outside world abreast of his life via Twitter, under the handle @Alig_Aligula. “I look just ADORABLE in my mess-hall whites & hair net,” Mr. Alig tweeted in March to his followers (he currently has 29,500). “Where are the paparazzi when you really need them? #saycheese.”

And since his release 10 days ago, Mr. Alig has been chasing the media spotlight whenever he can, giving interviews to The New York Times, Vanity Fair.com, People.com, Huffington Post Live, Inside Edition, Rolling Stone, Deadspin and The Daily Beast. The story of the Club Kid murderer, which spawned not one but two movies, including the 2003 feature film “Party Monster” starring Macaulay Culkin, continues to fascinate.

“People are crazy interested in Michael,” said the night-life veteran Steven Lewis. “It’s like a wreck on the highway. This club kid who almost changed the world. Will this really be a second coming? Or is he just a murderer?”

But first, Mr. Alig had to avoid being rearrested. The guards eventually decided to confiscate the digital-memory card from one cameraman who was filming a documentary (another crew was shooting a pilot for a reality TV show) and to allow Mr. Alig and his entourage to drive off.

In six hours, Mr. Alig would be back in New York, to try and reclaim the fabulous life he once had. “What I am most excited about is taking a shower without my clothes on,” he said. Prisoners usually shower in their boxers, he explained. “If you don’t, the other prisoners think you’re disrespecting them. They’re homophobic.”

BEFORE HE WAS SENTENCED to 10 to 20 years in 1997 after pleading guilty to manslaughter, Mr. Alig was a cult hero to a misfit band of partygoers — closeted teenagers, drag queens, performance artists, trust-fund brats — who called themselves the Club Kids.

His crew of freaks, with their plastic lunch pails and polka-dot unitards, ruled over the big clubs of the late 1980s and early ’90s, places like Limelight, the Palladium and Tunnel. His best-known party was the Wednesday-night Disco 2000 at Limelight, which once featured a hospital-theme with uniformed nurses and bloodied doctors who doled out vials of the club drug Special K.

“Michael came at the end of a cycle in New York,” said the night-life impresario Rudolf Piper, who gave Mr. Alig his first job as a busboy at Danceteria. “Warhol had left the scene, and there was a void of celebrity, and Michael turned these nobodies, and himself, into celebrities.”

Behind bars, Mr. Alig kept up his role as a twisted Little Lord Fauntleroy. He said he got hundreds of letters from closeted and alienated kids who identified with him, or at least the version played by Mr. Culkin. “Congrats on forever altering club life, attempting to reinforce self worth from demolishing conventional styles and attitudes,” he quoted one gay teenager as writing. Star-struck inmates idolized him, giving him drugs, food and clothes, he said.

One day this past March, with a foot of snow on the ground, he breezed into the prison cafeteria, which doubles as the visitors’ room, with vending machines humming in a corner and a sad mural of Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse on a back wall.

He wore nylon drawstring pants and a crisp white polo (“prison chic,” he said), and looked surprisingly fit for someone who, according to a prison official, had spent more than five years in solitary confinement for heroin use (he says he has been clean since 2009). His face looked fresh and well rested, his hair was given a jailhouse Caesar cut, and his biceps and shoulders were buffed, thanks to a “cute boy” he met who is studying to become a personal trainer.

“I told him, ‘If you can whip me into shape in the next six weeks, I can introduce you to people in New York when you get out,’ ” he said.

Although he had seen the Internet only in movies, and through printouts of web pages mailed to him, Mr. Alig has the best-laid plans for life on the outside. “I have 200 ideas,” said Mr. Alig, a manic talker and jittery man-child who provides his own laugh track of constant giggles.

Many are reality TV shows that revolve around being a club kid today. His concept for a “Project Runway”-like contest: “You have 15 minutes and anything in a deli to create a fabulous outfit,” he said. He plans to pitch that one to Vice Media.

His spin on “America’s Next Top Model”: take two wannabe club kids from Podunk towns and with no money, plunk them down in New York with $1,000 and see if they can thrive “on being fabulous,” he said. “They may have to prostitute themselves. We had to. Maybe I, per se, didn’t.” That one goes to MTV.

While those ideas incubate, he is writing a memoir with Ms. Haynes, cheekily titled “Aligula,” chunks of which he has scribbled with pen and paper (and even toilet-paper rolls). Sample chapters have been sent to two literary agents, but no deal has been signed. The agents were concerned that the chapters didn’t express enough remorse, Ms. Haynes said.

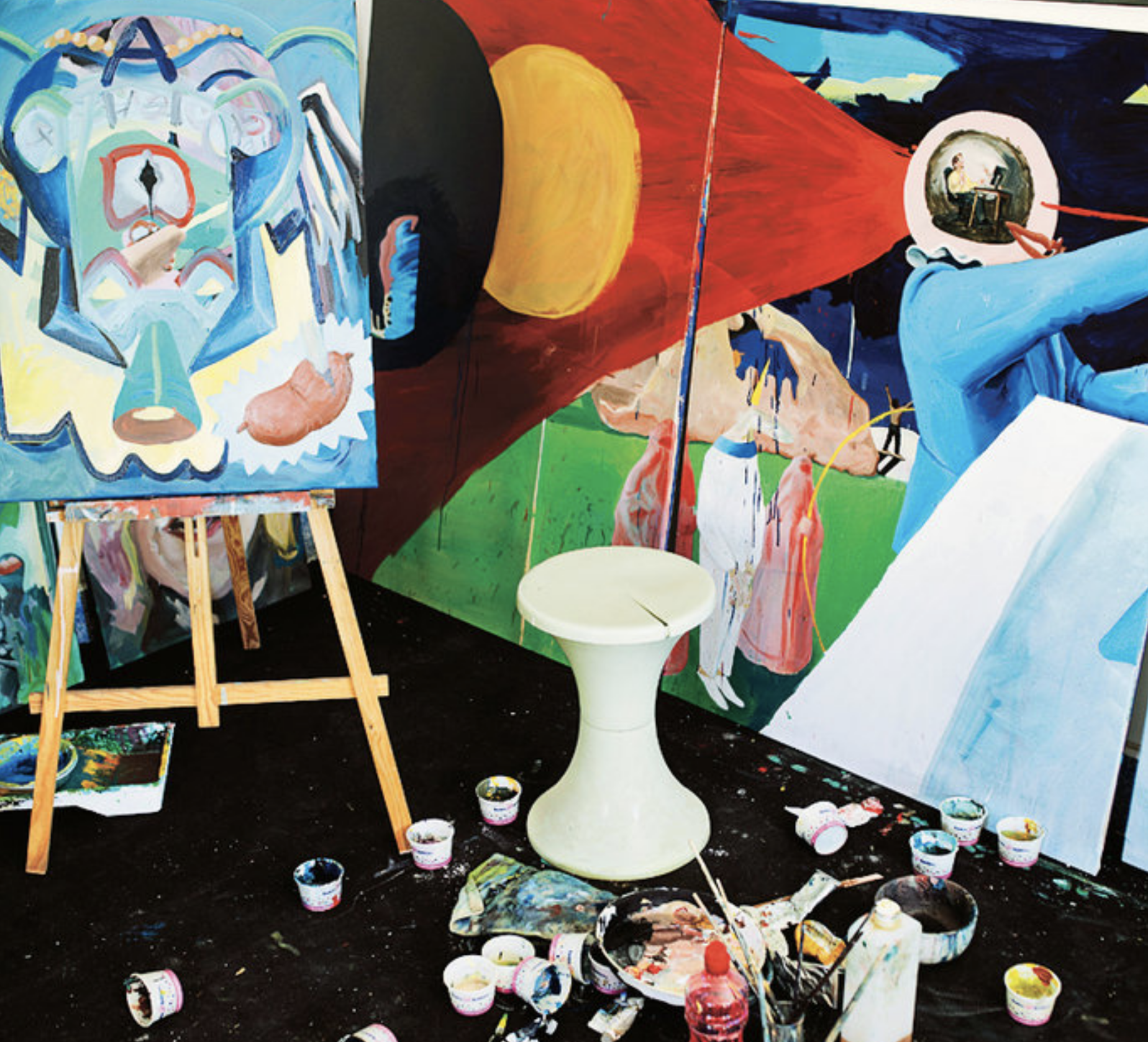

Mr. Alig also began painting in prison, “very Warholish” portraits of club friends like Amanda Lepore, Lady Bunny and RuPaul. He has done 260 paintings and wants to exhibit them, although no gallery has agreed to show them.

So his first order of business is to find a job. There was early chatter of Mr. Alig’s triumphant return to night life, but the conditions of his parole have made that impossible for now. He cannot drink or do drugs. He must submit to random drug tests and report to a probation officer once a week. And he has a curfew of 9 p.m.

To make some cash, he has a couple of writing assignments. He will write a blog about his re-entry into New York society for World of Wonder, a production company whose credits include “RuPaul’s Drag Race” and the original “Party Monster” documentary. He is also writing a monthly lifestyle column for Gay Times, a glossy magazine and website based in London.

And for the time being, home will be is the spare bedroom of Ernie Glam, a friend and former roommate from his Club Kids days, who is now a business journalist in Westchester County. Mr. Glam lives with his husband in a three-bedroom co-op in the Bronxdale section of the Bronx.

“I wanted him to know that I forgave him, and I want other people to know that I forgave him,” Mr. Glam said. “I am not forgetting the horrible things that happened, and nobody should. But you just have to not turn your back on your friends when they need your help.”

MR. ALIG’S OWN PLAN for redemption is less clear. He had approached the Hetrick-Martin Institute, which runs the Harvey Milk High School for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students, to donate proceeds from his art. But it declined his offer, he said.

Mr. Alig knows, and his friends have warned him, that people will want to hear about the killing from him, about why he did it. So on Monday, he recounted it in a first-person essay in The New York Post, titled “Club Kid killer relives bloody crime,” in which he professes “shame and disgust” and called himself a “selfish junkie who killed another human being.”

On a Sunday night in March 1996, Mr. Alig and Robert Riggs, known as Freeze, killed Mr. Melendez during an argument over money and drugs in Mr. Alig’s apartment on West 43rd Street. During a scuffle, Mr. Riggs hit Melendez with a hammer. Mr. Alig then suffocated him with a sweatshirt and poured Drano down his throat, he said, before dumping the body in the bathtub, pouring ice over it and abandoning the apartment for the next nine days. Then, high on heroin, Mr. Alig dismembered the corpse to get rid of it.

For nine months, with Mr. Melendez missing, Mr. Alig told people he had killed him, but no one seemed to believe him until the torso, in a cardboard box, washed up on Staten Island. (Mr. Riggs was released in 2010 on good behavior after serving two-thirds of his 20-year sentence.)

So does he think of himself as a murderer? “No,” Mr. Ailg said the other week before his release. “I think of myself as a drug addict who made some really, really, really poor choices, like the worst choices ever. But I wouldn’t say I’m a murderer because we didn’t wake up that day and say, ‘Let’s go kill Angel.’ ” He laughed at that. “I mean, you know, the distinction, it’s very slight. But in another way, it’s like night and day.”

He still blames the drugs mostly but, when pressed, places some blame on Mr. Melendez himself. “He focused on money,” Mr. Alig said. “There were layers of animosity because he was profiting on our downfall, on our addictions. And we really resented him for that.”

Not everyone has embraced his return. Michael Musto, the former Village Voice columnist who was one of the first to write about the case, recently penned an open letter to Mr. Alig for Scene, saying “You not only killed Angel, you basically murdered nightlife,” by giving the police an excuse to crack down on clubs.

Others have taken to Twitter to express their outrage. “Let’s not forget that Michael Alig (@Alig_Aligula ) is a murderer... R.I.P. Angel,” wrote @ShamisUltra. Which raises an unsettling question: Why are so many people celebrating the release of an admitted killer?

Victor P. Corona, a sociology professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology, said that Mr. Alig is a bona fide fashion icon, one who paid his debt to society and made a lasting contribution to culture. In a planned book, “Downtown Superstars: Inside Three Generations of New York Fame,” he makes the case that Mr. Alig is a bridge between Andy Warhol’s Factory and Lady’s Gaga’s fashion and music.

“They are all interested in culture and theatricality and spectacle, in transsexuals and hustlers, misfits and freaks — people considered on the margins of society who come together and say we, too, can have a community,” Mr. Corona said.

Others say that Mr. Alig presents a nostalgia for a pre-Gilded age, when club kids, not hedge-funders, ruled the city’s night life. “Their inspiration was ridiculousness,” said Fenton Bailey, a co-founder of World of Wonder. “It screamed childishness and gaucheness. It was very punk and deliberate and knowingly crass.”

Back in the van, as it pulled into Manhattan and down the West Side Highway around 5 p.m., Mr. Alig barely recognized a city transformed by 17 years of falling crime rates, development and luxury high-rises. He marveled at the bike paths (“God, now I have to start biking and being healthy”), at the Hustler Club with its faux-Greek facade (“Is that the magazine?”) and the tourists swarming Chelsea (“There used to be crack addicts and prostitutes over here”).

“I feel intimidated,” he said, as the van stopped outside the Almond restaurant in the Flatiron district, where a celebratory dinner was being held. Amid video cameras, he hopped out and hugged his friend James St. James, who wrote the book “Disco Bloodbath,” on which the movies were based. “I don’t recognize you,” Mr. Alig said to Mr. James, whose dyed-red hair had been replaced by a clean dome.

Inside were a dozen friends and supporters, including Mr. Glam and Mr. Corona. They laughed about old times, taught him how to use Grindr, teased about handling a knife in public and filled him in on gossip. At one point, Mr. Alig went to the restroom, and Mr. James joked that he was in there doing drugs, a rumor that made its way to Billboard, which called Ms. Haynes to check out the story. The item was squashed.

Mr. Alig ordered a pan-roasted Arctic char and a Coke. Then as the evening got going, barely 90 minutes later, Mr. Alig got up to leave. He had a curfew to meet.