Panic in Detroit

DETAILS MAGAZINE

MARCH 2001

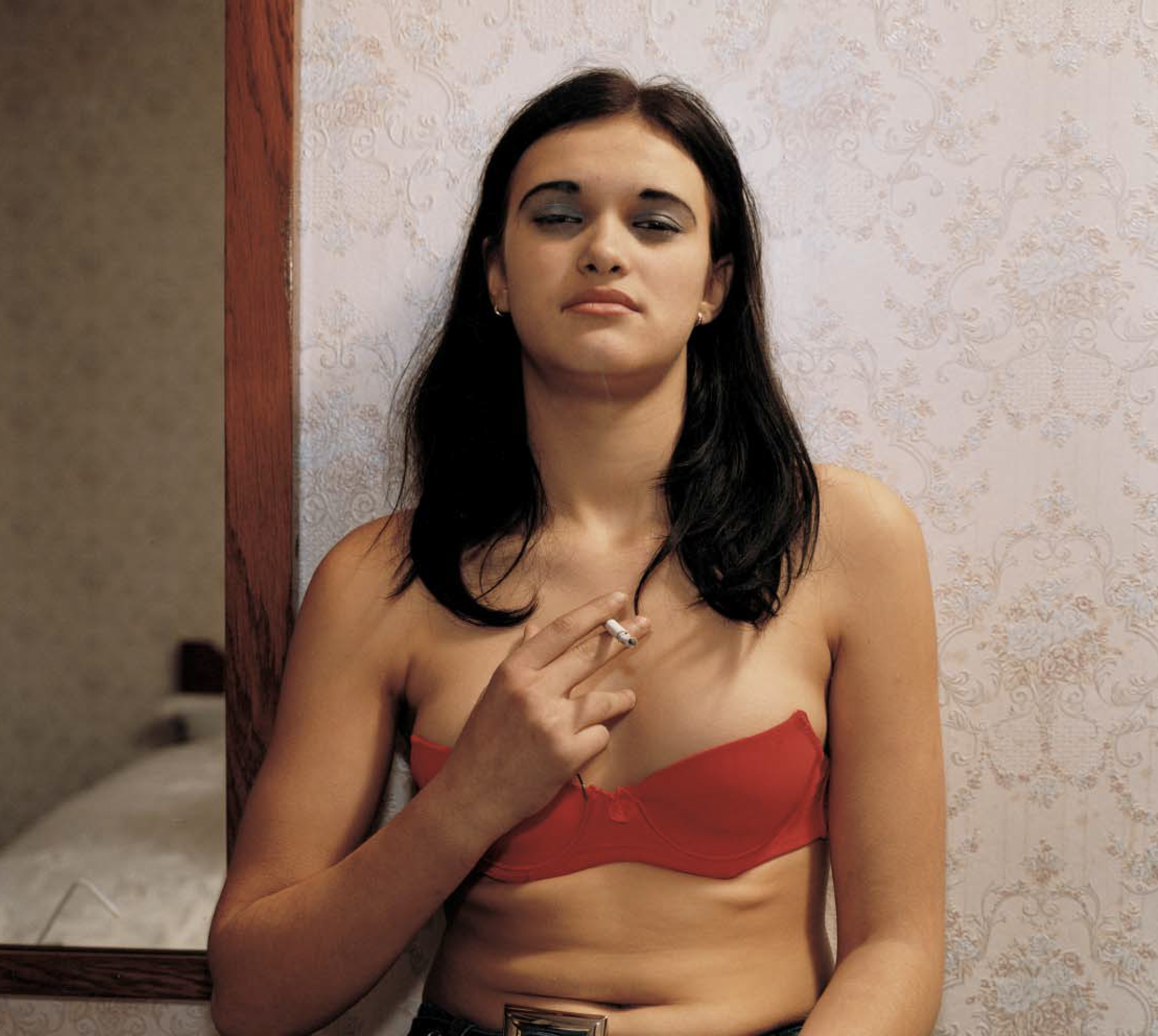

Photo by Stephen Barker

They called him Opie, but a less-than-Mayberry upbringing ensured that happy days weren’t in John Eric Armstrong’s future. Was the 27-year-old the Demon Barber of the U.S. Fleet, Strangling a girl in every port where the Nimitz dropped anchor? Later, cruising the streets of Motor City for prostitutes in his Jeep, Armstrong may have jacked his body count up to 27. But experts still wonder if he was quite as prolific—or horrific—as he’s claimed.

IT WAS 10 P.M. ON APRIL 12, quitting time for John Eric Armstrong, who’d recently been hired to pump 747s full of fuel at Detroit Metro Airport. But instead of going home to his pregnant wife and 15-month-old son in Dearborn Heights, a middle class suburb on Detroit’s western border, Armstrong pointed his bluish gray jeep Wrangler in the opposite direction and sped toward the city’s run-down southwest hide. Factory foreman at Ford and Chrysler lived here in pretty Victorians until the late sixties, when riots tore up the city and the area’s solid middle class pretty much left this neighborhood for dead, a valley of ashes with boarded-up storefronts, the scattered bones of old cars, and lonely corners haunted by wraith-like prostitutes.

A country boy from a small town in North Carolina and a former Naval petty officer with a couple of good conduct ribbons on his chest, Armstrong had learned to shop prostitutes during his time overseas. To wind up this chilly, overcast day, Armstrong was looking for a backseat bout of anonymous sex (or as much anonymous sex as you can have when the name you go by—Eric—is stamped matter-of-factly above your shirt pocket). And maybe he was looking for something more. Turning down a seedy stretch of Michigan Avenue, he’d later tell police, he thought he spotted a familiar face: an Asian-Hispanic beauty who liked to work in faux-cheetah boots and ass-baring skirts. Armstrong, a baby-faced 26-year-old whose childhood teachers jokingly nicknamed him Opie, drifted past Avon Skinner several times. He was blinking at her—in disbelief.

That night, Skinner—street name: Jasmine—was working her usual spot on the north side of Michigan, just west of the Venus strip club. Only 36 hours before, she had hopped into Armstrong’s car, traded sex for $100, and seconds afterward found a pair of meaty hands wrapped around her neck. Or so the 20-year-old testified later. Armstrong was growling, “I hate prostitutes.” Skinner blacked out. Two hours later, she awoke on the grassy shoulder of the Edsel Ford Expressway. Her purse was gone and her clothes were ripped. She had a four-inch gash along her hip. Though shaken, she hadn’t bothered telling the cops. “Even if bad shit happens to these women, they don’t want to draw extra attention to themselves,” says Brad Bullock, a police officer who worked the Michigan Avenue strip for five years. “Once it’s done, it’s done.”

But recent events were forcing police to pay more attention. Less than a week earlier, a train conductor near Conrail’s Livernois Yard had spotted the body of a woman splayed near the train tracks. Police found two more bodies at the foot of an adjacent slope. Their conclusion: A serial killer was on the loose—and he liked hookers. He would leave them in the grotesque poses, legs spread wide and arms positioned overhead, as if surrendering to a gunman. Bras were routinely shoved up around their necks, in some case, their eyes were open. Two days before, Devon Marus, a black transsexual prostitute, had fought off an attacker by blasting him in the face with pepper spray. She told the police about this baby-faced predator wearing a workshirt that read ERIC and his blue car—with “the rear tire cover that had JEEP on it,” she said.

Tonight the alleys of Michigan Avenue were panting with undercover cops. As Armstrong’s jeep moved slowly down the street, police spotted that distinctive tire cover and started flashing their lights. As he was loaded into the patrol car’s backseat for questioning, Skinner clicked across the street in her stiletto heels. She gazed at Armstrong through the patrol car’s window and he stared back flatly through his wire-rim glasses.

“That’s the motherfucker that dumped me on the lawn and took my purse and choked me out!” Skinner screamed, pointing.

Armstrong didn’t flinch. He’d been expecting this. He would later claim in a seventh-floor interrogation room at police headquarters that he wanted it to happen. He broke down, sobbing, and begged for mercy. “I need help,” he said.

Over the next fourteen hours, between cheeseburgers and Cokes and one fitful nap, a terrible tale emerged. Armstrong, who stands six feet two inches tall and weighs 230 pounds, claimed credit for strangling five Detroit prostitutes and confessed he’d attempted to kill four others. He revealed lurid details that only the killer would know: how he’d given one a split lip, how another wore leather, how he’d squeezed the life out of yet another and returned to have sex with her broken body.

His interrogators were stunned.

But Armstrong wasn’t finished. His torrent of macabre tales stretched back seven years. While serving aboard the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz, he killed at least 22 women in exotic ports around the world—Pattaya Beach, Tel Aviv, Hong Kong, and Waikiki—and in domestic pit stops Seattle, Norfolk, and San Diego. He told of running one hooker over with his car, throwing another from a window, killing yet a third after sex in a horse-drawn carriage. If all these stories were true, that would make Armstrong one of the most prolific and well-traveled serial killers ever.

This month, Armstrong is on trial for the murder of gas-station and mini-mart manager Wendy Jordan, 39. Not only is Jordan’s case the strongest against Armstrong, it may be the most outrageous, for it was Armstrong himself who reported finding Jordan’s body. If convicted, he faces mandatory life in prison. In dozens of hand-wringing letters to his wife, Katie, from jail, Armstrong makes some surprising claims, some of which his lawyer says will be used in his defense: that as a child he watched his father beat his mother; that his father forced him to perform oral sex on him (and vice versa); that he feels responsible for the death of an infant brother (whose body he says he found when he was 6 years old); that he thinks if he had been born a girl, his father would not have abandoned the family. Armstrong’s attorney, Robert Mitchell, has challenged his client’s alleged confessions, arguing that police coerced them by threatening to take away his son, Austin (a charge police deny). If Mitchell does not succeed in suppressing the confessions, he will argue that Armstrong, suffering “childhood flashbacks” from his father’s alleged abuse, was temporarily insane at the time of the attacks. But former members of the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, which profiles serial killers for the bureau, caution against falling for these calculated soliloquies citing all sorts of (often falsified) abuse and performed for a culture steeped in gestures of confession and redemption.

While reporting this article, Armstrong grated me an exclusive interview. I spoke with his mother, his wife, the Detroit Police Department, the Wayne County prosecutor’s office, and the FBI. The Wayne County Jail, where Armstrong is currently on suicide watch, would not allow me to visit him. In defiance of his own attorney, he spoke with me by telephone and mailed me a 30-page history of his childhood, his time in the Navy, and his own account of what happened on the streets of Detroit during his self-confessed reign of terror last spring.

John Eric Armstrong was born on November 23, 1972, following 36 hours of labor culminating in a difficult Caesarean section; he was stuck side-ways in the womb. He grew up in a rented trailer in Bridgeton, North Carolina, home to employees of an auto-parts plant, a paper mill, and large berry-picking fields on the outskirts of town. His mother, Linda, married a young Marine, John Ezra Armstrong, after he showed up her Ohio doorstep with her older brother. “They were just a nice, respectable family,” says Jerry English, pastor of the 350-member Antioch Baptist Church. “A little on the struggling side, but decent folks.” In 1978, Armstrong was honorably discharged from the Marines and became an electrician. Linda was a geriatric nurse and sometime Avon Lady.

On the outside, says Linda, he “acted like Good Guy Joe.” But he wasn’t. Family members and friends note that John often yelled at his wife or exploded at remarks he found “stupid.” One former neighbor says he beat her, often right in front of Eric (who eventually dropped his first name). “I remember walking in on my mother and father in the bedroom,” Armstrong writes, “He was hitting her and strangling her.”

Armstrong’s attorney says the defense will explain how Linda wasn’t the only one being abused. When he started dating Katie, the woman who would become his wife, he told her how his father beat him with a black belt until he raised welts on his buttocks and legs. Armstrong now says that his father began sexually assaulting him in October of 1978. At night, he claims, the former Marine would creep into his room stick a finger in his anus or perform oral sex on him, then demand the son do the same. “My father would say, ‘Come here, boy,’ with this big old smile on his face,” Armstrong told me. “He’d force me down to my knees and sometimes he’d make me suck it and kiss it.” Armstrong says he never told his mother because “I was scared that he would hurt me more, or hurt my mom. And I felt dirty.”

Linda claims she never knew her husband to physically abuse her son. These reports are impossible to verify as Armstrong senior has not been seen by friends in a decade. Attempts to locate him in his Oklahoma hometown led to a trail of disconnected phone numbers and invective.

The family situation further deteriorated when Paul Michael Armstrong was born in November 1978. Eric was 6, but his little brother “was his baby,” Linda says. “He’d sit and feed Mikey and constantly fuss over him.” One night, in January 1979, when Mikey was 2 months old, Armstrong says he found his little brother dead in his crib. Then he crept back to bed and feigned sleep. The coroner’s report states the cause of death as SIDS, sudden infant death syndrome. In a recent letter to his wife, Armstrong suggests this may have been his first victim. “There is no way I can live with that guilt,” he wrote. “Knowing that I killed my little brother, without knowing it.”

When John Ezra Armstrong did leave his family, he told friends (and later his son) that it was because Linda was cheating on him with Ron Pringle, a truck driver whom Linda later married. But Linda says it was John who cheated on her with a Georgia waitress he actually committed bigamy with.

If Armstrong’s home life was unsettled, he worked hard to keep outsiders appeased. His teachers found him painfully shy, obsessively polite (if not particularly bright). Classmates called him a mama’s boy because he hung out with girls: When pushed or punched, “he would never take up for himself,” says Chris Dearien, Armstrong’s schoolmate from kindergarten through the tenth grade.

Outwardly effeminate, Armstrong also seemed prudish. As a teenager, he had a platonic friendship with one girl, but she pressed him for sex. “Eric wasn’t ready,” says his mother. Instead of hurting the girl’s feelings, Armstrong wrote her a letter explaining that he had AIDS, Linda recalls. If they slept together, he said, she could die.

The girl was so upset that she told her parents, who called Linda. During a heated argument with his mother over the call, Armstrong grabbed a knife, locked himself in the bathroom, and threatened to kill himself. The standoff ended when paramedics talked him out and whisked him off to a psychiatric ward at the local hospital. He stayed there for a month. Afterward, he went to a therapist regularly after school.

By the time he reached his senior year, in 1991, Armstrong was a full-blown recluse, a man-child lumbering on the margins of the school grounds. “He was jut like a big Lurch,” says schoolmate Tony Heckman. “He didn’t seem to have many friends.”

Looking for a way out of his isolation—and hoping to earn money for college—Armstrong joined the Navy. He was assigned to the USS Nimitz, stationed off Bremerton, Washington. He was an unremarkable sailor: He worked in the ship’s laundry for two years and then in the barber shop for a year and a half, both of which were considered sissy jobs. During their first Pacific tour, the ship docked in early July 1993 at Thailand’s rowdy Pattaya Beach. There, shipmate Murray Comly says, he taught Armstrong to drink. Armstrong also developed a taste for prostitutes. “I seen him one night and he had, like 42 hickeys all over him,” says Comly, who noted that Armstrong bragged about his conquests.

Armstrong, says Comly, was one of a group of sailors on the Nimitz who saw the Navy as little more than a floating sex tour. The goal, says Terry Woods, a petty officer who worked alongside Armstrong in the ship’s barber shop for nearly two years, was “to meet the hundred mark—sleep with 100 hookers.” Armstrong had claimed in his confession to police that while in Thailand, in 1993, he became so enraged after paying for sex with a transvestite that he killed him by tossing him out a window. An FBI investigator assigned to this case told Details that on the same night, Armstrong returned to the ship an hour late with his face cut up and bleeding. A senior officer noted it and filed a report.

Because he was so unthreatening, Comly says, the ship’s women frequently used Armstrong’s shoulder to cry on when they were fighting with their boyfriends. But Armstrong could also be a hothead, especially in the barber shop.

“The supervisor would come in and say, ‘This space isn’t clean,’ after we just cleaned it,” says Woods. Armstrong would have a tantrum, throwing things around. “He’d say, ‘I wish I could kill,’” Woods adds. Other times Armstrong would retreat to the rear supply closet and sit in the dark for nearly an hour.

In March 1997, Armstrong fell in love with fellow shipmate Katie Rednoske, a petty officer, first class, and a member of the crew’s aircraft fire-and-rescue squad. They became inseparable. Once a week they’d sneak into the barber shop to have sex in the chairs, Katie told me. They went sightseeing in every port, snapping photos of each other riding camels in the Arab desert, touring the king’s Grand Palace in Thailand. For a time Armstrong gave up drinking and claimed he had sworn off hookers. He bought his beloved Baby Doll—that’s what he called her—Winnie the Pooh bears; he would wear Winnie the Pooh socks from K-Mart.

But while Katie could be a comfort, she also had a way of bludgeoning Armstrong’s feelings, friends say. She criticized his “redneck” haircuts and dismissed his “hillbilly” wardrobe. She chided him for being too passive. “It was a real love-hate relationship,” says Woods, who recalls Armstrong ranting bitterly about Katie for hours at a time. “He’d just say she was a real ball-buster.”

Katie Armstrong, 25, is dressed in faded jeans and doubled-up pullovers with a pair of battered Birkenstocks on her socked feet. A compulsive talker, she rarely stops to catch her breath. And she is not supposed to be talking to me at all.

Katie refused all interview requests—until now. Since Armstrong’s been in jail, she says, she lost her job as a lifeguard at the local YMCA because of the publicity in the case. She now works at a local donut shop. Katie teeters between disbelief that Armstrong did this and a sneaking suspicion that it’s all true. She tosses out vague exculpatory theories: Eric wouldn’t be able to pick up a dead boy, she says, because he has carpal-tunnel syndrome from his days as a barber. She’s mad at Eric “for pulling a stunt like this.”

But in the next breath she reverts to blind faith in his innocence, unable to wrap her mind around the idea that the man she loved had killed so many women. “My husband is the kind of person who cries when he sees a dead animal in the street,” Katie says. “If you yell at him, he cries.”

In the spring of 1998, the Nimitz docked at Norfolk, and Katie and Eric moved into a small Navy-owned apartment with a friend across the bay in Newport News. Armstrong got Katie to take out a loan so he could buy a bluish-gray Jeep Wrangler with a soft zip-on top.

Around this time, Armstrong started to display a fetish for role play, says Katie: She would be the hooker and he would be her john. He bought her a leather skirt, bra, and fuzzy handcuffs: “He’d say, ‘How much for sex?’ And I’d say ‘You can’t afford it.’” Occasionally, he liked to hurt her, too. “But not bad.” Sometimes he’d squeeze her too hard.

The couple married on September 25, 1998, and had their first child, Austin, the following February. That spring both decided not to re-enlist, discouraged by their slow movement upward, and by Armstrong’s emerging weight problem, for which he was often reprimanded. Armstrong found it difficult to raise a family in a one-bedroom apartment working odd jobs. He pinned his hopes for a future on joining the North Carolina State Troopers, but they turned him down in 1999 after a former shipmate he used as a reference mentioned his temper. Then the Virginia State Troopers rejected him because he was 17 pounds overweight. With money tight, the young family retreated (despite Armstrong’s protests) to Katie’s parents’ house in Dearborn Heights, Michigan.

Armstrong took a job as a guard with Initial Security, and he signed up for law-enforcement classes at a community college with hopes of eventually entering the U.S. Marshals or the nearby Border Patrol. “Many serial killers are police groupies,” notes Northeastern University criminologist Jack Levin. “Son of Sam loved wearing uniforms. John Wayne Gacy had a police radio in his car and a siren. Kenneth Bianchi, the Hillside Strangler, was in Sheriff’s Reserve. The attraction is power, authority.”

Armstrong may have enjoyed his uniform, but he hated Michigan and his living situation. Though grateful to his in-laws for their support—and always ready to cook, clean, and cut grass—he was humiliated by his indebtedness. He began hanging out at strip clubs and drinking a lot of Budweiser. He began to cruise the Detroit streets for prostitutes.

With its open-air carnival of drugs and sex for cash, Michigan Avenue, a quick ten minutes away, attracted Armstrong’s attention. It didn’t seem to matter if they were young or old, ugly or beautiful, white or brown, or doing it for $40 worth of crack, Armstrong picked them up. His activities further drained the family’s meager funds. To complicate matters, he now insisted Katie dress up as a prostitute every time they had sex. “He couldn’t have it any other way,” she says.

Armstrong claims that because a high-school sweetheart cheated on him with his own cousin, he had grown to distrust women—even his own wife. “Katie said she didn’t want to have sex for two years because the pill would make her fat and condoms made her dry, and I thought that was bullshit,” Armstrong told me. On August 15, 1999, Armstrong told police, he pulled his car up to a leggy blonde prostitute name Natasha Olejniczak. After agreeing to pay $100 for intercourse, he drove her to her room at the Days Inn. Dressed in knee-high leather boots, the 26-year-old wore a shirt tied up under her breasts, and her “cheeks”—as she says—hung free in what could barely pass as a skirt. Armstrong, she told the court, seemed like a gentle, shy man who “was very nice about everything.” But once inside the room, he turned nervous and panicky. He hadn’t wanted to go to a motel in the first place, Olejniczak says, but she’d insisted.

Armstrong paced a moment, then asked to use the bathroom. When he came out, he said, “I gotta go. I don’t feel right in here.” He left, but a few minutes later he knocked on the door, Olejniczak says. She opened it. Slamming the door behind him, Armstrong pulled out a folding knife, she says.

As she backed toward the bed, she claims, Armstrong pushed her down to the floor. She wrestled for the knife, cutting her hands in the process. Armstrong then picked her up and wrestled her to the bed, she says, pressing his knees into her chest. “I hate hookers,” he hissed as he began choking her. She passed out. She came to several hours later on her knees, her forehead pressed into the bed, a bloody telephone cord wrapped around her neck.

When the police arrived, they found one odd clue: Lying on the floor was a brown belt buckle with an insignia. It was only after Armstrong was busted that investigators identified the buckle as part of the Initial Security uniform, says county prosecutor Elizabeth Walker.

It takes about two minutes of strangling for a victim to lose consciousness. But it can take another five minutes of squeezing to actually kill a person. That’s a long time to look someone in the eyes. Criminologists say strangling is the most intimate form of murder; serial killers have bragged about feeling an ebbing heartbeat beneath their fingers.

By his own accounts, and those of his survivors, Armstrong faced every one of his victims. He’d move quickly; one minute he’d be shy and polite—even giggly—the next, he was like a python wrapped around their necks. His face would turn red, and he’d get so close the hookers could feel his breath. There was no teasing, no menacing, no making the victim squirm in anticipation of her death, which was the M.O. of Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer. Each time, Armstrong told police, he saw his father’s face.

“The common theme is playing God,” says Gregg McCrary, retired supervisor of the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, “making the decision whether this person lives or dies. A lot of time, it’s compensating for lack of control in their own lives.”

Throughout the fall and early winter of 1999, a half-year before Armstrong’s eventual arrest, the screws began to tighten. Katie says he struggled with school, earning mostly below-average grades. “Target cut my hours from 40 to four,” says Eric, who worked part-time in sales, “and every time we saved up, something happened, like my muffler blew.” Though he reveled in being a father (“Eric’s father abandoned him, and this was like his second childhood,” says Katie), he feared for his son’s health. That winter, Austin needed surgery to correct a congenital defect that left his urinary tract crimped. Armstrong feared he might die, just as brother Mikey had, around the holidays.

On November 3, while guarding a medical office building in neighboring Novi, Armstrong called the cops at 1:30 a.m. to report that he’d just fought off some robbers. They’d smashed a glass door and slashed his face in the scuffle, he said. It didn’t take long for the cops to figure out the report was a sham. “When I pressed him, he broke down crying and admitted it after fifteen minutes,” remembers Novi detective Victor Lauria. “He had cut himself with a scalpel from one of the offices; he showed us where he threw it in the Dumpster.” He was later charged with falsely reporting a felony, itself a felony count. (The charge is still pending.)

Twelve days after the false report, Katie came home to find Armstrong blacked out on their canopy bed. He had swallowed a bottle of Comtrex, an over-the-counter allergy medication, with half a bottle of Budweiser. Doctors pumped his stomach. Ashamed—and dispatched by his in-laws to a psychotherapist—Armstrong picked up a prostitute on Michigan Avenue on December 3, he later confessed to the police. After paying her $50 for sex, “I started strangling her. I don’t know why.” A passing motorist later spotted Monica Johnson’s body lying face-up in an alley.

On January 2, Armstrong attacked Wendy Jordan, police say, and threw her in the Rouge River. But Armstrong couldn’t wait for police. This time, he pretended to find the body.

It was around five o’clock, he told police, and he was driving home from Target. Feeling nauseated, he pulled over on the shoulder of a bridge, leaned over the wall, and spotted Jordan’s body.

But the story made no sense: A neighbor had seen Armstrong stroll from his car rather calmly—and not get sick. Why, cops wondered, would somebody get all the way our of a car to get sick? Why walk around to other side of the car?

At the police station, investigators grilled Armstrong. “You’d expect an innocent man to say, ‘Whoaaa! Hey, I just found the body. I just did you guys a favor. What are you looking at me for?!” says Don Riley, a Dearborn Heights detective. The police suspected they had their man, but after four hours, they had to let him go for lack of evidence. Why would he do such a thing? Experts on serial killers say he may have been trying to gain attention for his work. There was, too, the bonus of finding-the-body publicity. Or he may have wanted to help play detective, since Armstrong, like many serial killers, wanted to be a cop.

Before he drove off, Armstrong allowed the police to take fiber samples from the jeep’s carpet. Within weeks, the state police crime lab had matched them with those found on Jordan’s tights. Minute golden flakes from Jordan’s high heels were also found in his passenger-seat carpet. But it wasn’t enough to haul him in. Ultimately, his blood sample’s DNA matched sperm taken from Jordan’s rectum, but police encountered delays in procuring a warrant for his arrest.

Armstrong tells me that he did indeed have sex with Wendy Jordan. But he says he doesn’t remember killing her: “All I remember, after that, is I’m sitting next to Katie on the front couch watching football. I don’t even remember what teams were playing.”

In late March, 2000, Katie Armstrong announced she was pregnant with their second child, a girl. Eric said he was thrilled. But Katie thinks the news troubled him. “Eric was always worried that he wasn’t being a good provider,” she says. Katie pressured him to save more money so they could move out of her parents’ house. Sometimes the arguments were fierce. She would remind him how much he owed her, for living in her parents’ house, for co-signing the loan on his Jeep.

Was Armstrong merely angry at Katie and taking it out on the hookers? “What these killers tell us—and they’re so consistent,” says McCrary, “is that killing is a great stress release for them. They kill somebody, they feel better.”

Sometime in late March, according to statements he gave police and letters to his wife, Armstrong’s life nosedived into frustration and rage. It would eventually culminate in an alleged three-week spree of attacks on five women that would leave three of them dead. Wilhemina Drane, 42, a car-parts packer and “retired hooker” with a hair weave, told Details she was waiting for a bus on Michigan Avenue but accepted a ride from Armstrong at around 11 p.m. He pulled his Jeep over to the side of the road to get something out of his coat but, she says, reached for her throat instead.

“Lucky for me, I had a scarf on,” Drane says. “So he couldn’t get the best grip.”

Drane knocked Armstrong’s glasses from his face and scratched him. But he hung on tight. On the verging of blacking out, Drane says, she blasted Armstrong in the eyes with a can of pepper spray concealed in her coat. Then she leaped from the car. “I said, ‘Fucker, I ain’t ready to go,’” recalls Drane. “I ain’t the one.” Then she ran.

A week later came Rose Marie Felt, 34, a vivacious blonde streetwalker from northeastern Detroit who struggled with crack addiction. The cops found Felt at the bottom of an incline in the Livernois Yard. He black tights were crotch-less, a detail Armstrong shared with police. After they had sex in the Jeep at the railroad tracks, he told cops, he strangled her and pitched her down the twenty-foot slope, only to scuttle down after her and have sex with the body. Necrophilia, says the criminologists, is the ultimate form of control. But it’s relatively rare; Bundy and Dahmer did it. “Necrophilia is about having a sexual partner who is entirely compliant, makes no demands, never rejects. It allows one to have total control,” says Park Dietz, a professor of clinical psychiatry and behavioral science at the UCLA School of Medicine.

One week after Felt was slain, Armstrong has said, he was back on the tracks again around midnight, with Kelly Hood. “I shouldn’t have been with her,” he whined to police. “I dislike them because women shouldn’t be doing that. I get angry and hostile. I lose control,” he says in the same therapyspeak that peppers his letters. Armstrong says he strangled Hood just twenty feet from where Felt’s body lay rotting in the weeds.

Three days later, on April 7, Armstrong pretended to look for his money as he reached for Devon Marus, she testified. Avon Skinner says she followed two days later. It was getting to be a busy week.

While stress undoubtedly triggered this murderous orgy, criminologist Jack Levin says the crimes were bound to increase, comparing killing to binging on a drug. Gregg McCrary says serial killers describe murder “as a sort a very euphoric rush, better than sex, better than drugs, better than anything.”

Katie claims not to know where her husband was on any of these nights. “I don’t want to know,” she says. “I guess I’m just afraid. I’m afraid of Eric’s answer.”

I ask what that answer might be.

“Oh, that he was looking at prostitutes,” she says resignedly.

On Monday, April 10, he was out at 1 a.m., “looking to get laid,” he says, when he came across Nicole Young, hanging out between two car lots on Michigan Avenue. Five foot six and 20 years old, she would be the youngest—and the last—of the railroad track victims. Armstrong told police he was “very angry, very upset” that she offered him sex for money. He said that as soon as she named her $60 price, he wanted to hit her. After they had sex in his backseat, Armstrong claimed, Young started to make fun of him. “She said I had a small penis and didn’t know how to use it,” he told investigators. Enraged, Armstrong grabbed her white panty hose and strangled her. He says he threw the used condom out the window on the drive home.

Levin says that is seems unlikely that a hooker would humiliate a john in this way. “He’s telling the story to gain sympathy,” he says. “He wants the guy who’s listening to him, the cop or whoever, to feel sorry for him. But everything with these guys is a stage act.”

After Armstrong disgorged Young alongside the Jeep, he told police, “I just remember taking off and seeing her lying there through my rear-view mirror.”

But he didn’t just toss these women away after killing them, as he’s repeatedly insisted. What he did, say experts, was far worse. Killers who feel remorse often hide their victims, partially burying them, sometimes placing symbols of comfort, like pillows, nearby, or rearranging their clothes. But leaving bodies exposed and bare, and sexually vulnerable—and the victims were uniformly arranged in the same undignified position—sends a message. “It says, Look at these women,” explains Roy Hazelwood, author of The Evil That Men Do and a retired FBI profiler.“Look what they are.”

Following Armstrong’s arrest, his tearful face was broadcast around the world. Police from several nations journeyed to Detroit to hear his stories, hoping to match them with unsolved cases. The FBI dispatched dozens of attachés to such far-flung ports as Singapore, Bangkok, Waikiki, and Tel Aviv. It turns out that Armstrong’s ship was almost always in port when and where he said it was. That doesn’t mean some agents aren’t wondering whether he inflated his body count, as is common with serial killers. The FBI will not release details of most of those confessions since Armstrong has not been charged in any of the overseas cases. They will only offer a laundry list of cities and dates. Even so, it’s unlikely that any other country will lay claim to John Eric Armstrong; there is no strong physical evidence linking him to any of those bodies.

Police believe Armstrong’s career kicked off in Pattaya Beach in July, 1993, as he ricocheted around the Pacific. It touched down in Honolulu, where, he told police, he killed a prostitute in a hotel room; it made stops in Seattle, where he claims he used a lead pipe to bludgeon a man who tried to bum money off him. There were other claims of murder in Hong Kong and San Diego and Norfolk, Virginia, where, he told police, he ran a hooker over in March 1998.

After Armstrong’s confession, Norfolk police checked their files and found a seeming match: Linette Hillig, 34, a prostitute dumped behind a bingo parlor, exactly as Armstrong described, on March 5, 1998—two days after he bought his Jeep. Hillig’s body had indeed been run over. Officially, Norfolk police will only say that they haven’t ruled Armstrong out as a suspect. But an FBI agent close to the case, who spoke on condition of anonymity, says local police are prepared to file charges against Armstrong following his trial in Detroit. And Virginia has the death penalty.

Armstrong says he didn’t kill anybody. But when I press him—when I ask how, amid all the physical evidence—he he can say this, he opens the door a bit. “I could have done it,” he allows. He hesitates a moment. “But I don’t think so. I’m not a violent person.”