Brave New World

DETAILS MAGAZINE

SEPTEMBER 2006

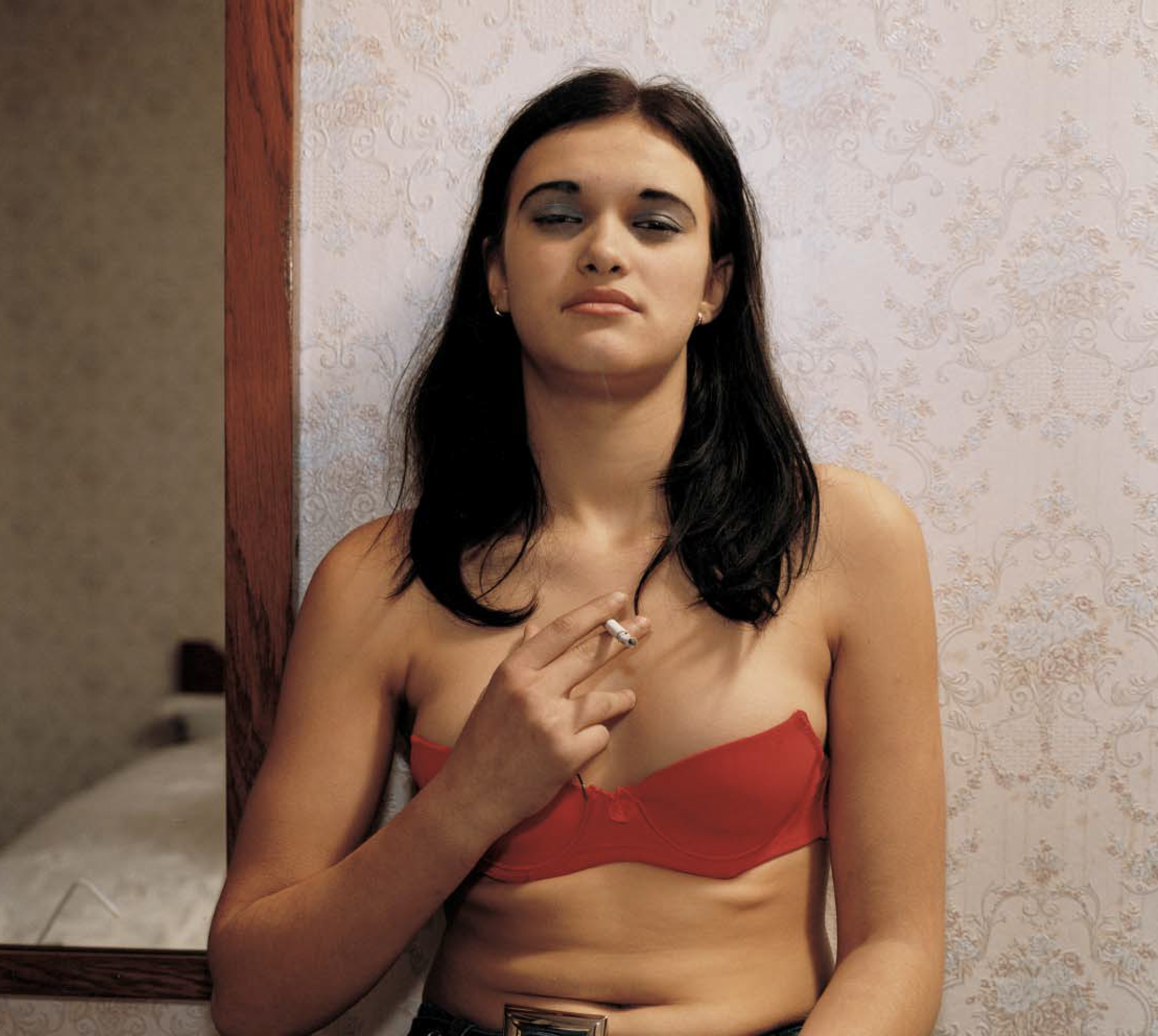

Photo by Aaron Huey

Not far from the Wounded Knee Massacre site in South Dakota, another battle is raging as Lokata youth struggle to choose between ancient traditions and gang warfare.

AT SUNSET THE BASKETBALL COURTS NEAR THE POWOW GROUNDS ARE a mess of beer cans, trees tagged with gang symbols, and trash struck in the chain-link fence. Marty Red Cloud and two friends, Daniel Standing Solider and Steve Yellow Boy, are regular players here. There are other courts closer to where they live, but the Tre Tres, one of about a dozen gangs on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, often start trouble up here, so Marty and his friends tend to avoid them. A few days ago Daniel was hanging out in Marty’s front yard while Marty ran an errand. Daniel says a few Tres spotted him and attacked him, breaking his hand with a bat.

Marty, a 22-year-old high-school dropout, belongs to a gang called the Wild Boyz. A few years ago they were what cops called the peewees, a few ambitious teens who had split from a larger adult gang, the Nomadz, to forge their own identity. The Nomadz were heavily involved in coke dealing and prone to fighting, but many of them have “aged out” of gang life, meaning they’ve either started families, gone to prison, or simply died from drugs, violence, or drunk driving. Meanwhile, the Wild Boyz, with about 60 members, are poised to become the most influential and possibly the most dangerous gang in town.

“Everybody think they got to prove something,” Marty says, rolling a thin joint on a wooden bench while Daniel shoots baskets and Steve plays defense. “Think they gotta be stronger than us, but they can’t, because they need alcohol to give them courage. They can’t just step up.”

A beat-up Camry slowly cruises past the basketball court. The front grill is crumpled and somebody has smashed the windows, a typical act of gang retribution. The guys inside glare at Marty and his friends, and the ball stops bouncing as they stare back. “Pussy Tres,” Marty says as the car glides past. “See what I’m saying? Ain’t gonna do shit long as we together—and they ain’t drunk yet.”

Most Pine Ridge gang members take their style from hip-hop, wearingdo-rags, XXL tees, and college-basketball jerseys. Marty isn’t like that. He has a faint Fu Manchu and a wispy goatee that crests like a wave under his acned chin. He wears his Wild Boyz colors—black, white, and gray—subtly, in the form of Raiders shirts or other clothes. Most of the gangs on the rez ape national gangs such as the Bloods and the Crips, and will even borrow their names. The Wild Boyz seem to have no connection to any other gang; they’re a pure product of Pine Ridge.

“Our clique is about our culture,” he says, “about being a man, and a warrior.”

Marty is the great-great-great-grandson of a Lakota chief named Red Cloud, a famous warrior and statesman. In 1866, Red Cloud began to beat back the U.S. Army as it was building forts in the heart of Lakota country in presentday Wyoming. He helped secure treaties for the Indians and was the man who

settled the tribe here in Pine Ridge. Marty’s grandfather, Oliver Red Cloud, is the chief of the Oglala Sioux.

In Lakota tradition, Marty is expected to take part in a “sweat” tomorrow, a ritual of prayer and purification held in a sweat lodge, to prepare him for his first sun dance. The sun dance is a ceremony meant to purify the tribe. It represents life and rebirth, and for Marty it will also acknowledge his entry into adulthood. Marty’s best friend, Clayton High Wolf, who helped found the Wild Boyz six years ago, is the nephew of a Lakota medicine man and has invited Marty to dance at the ceremony, four days from now.

A sun dancer is supposed to prepare himself for a year. He attends sweats, meditates, and undertakes a vision quest, in which he must spend four days and nights alone on a secluded hilltop with no food or water, only tobacco and his pipe. Once he has achieved his vision, he takes his pipe and tobacco to a medicine man, who smokes it and interprets the vision. Marty has done none of this but still wants to dance at the sun dance, at Clayton’s urging.

At a sun dance, the medicine man pierces each dancer in the chest or the back with wooden pegs. The most sacred part of the ceremony, this symbolizes the sacrifice that the man is about to make for the good of the tribe. While other tribes also hold sun dances, the Lakota are the only ones who pierce.

Since they are considered the warriors of the Indian nation, they must endure the ordeal for all Indians. The medicine man then attaches ropes to the two piercings in the back, each weighted down with buffalo skulls. While others chant, the warrior dances in a circle, dragging the skulls in the dirt until his do-rags, XXL tees, and college-basketball jerseys. Marty isn’t like that. He has a faint Fu Manchu and a wispy goatee that crests like a wave under his acned chin. He wears his Wild Boyz colors—black, white, and gray—subtly, in the form of Raiders shirts or other clothes. Most of the gangs on the rez ape national gangs such as the Bloods and the Crips, and will even borrow their names. The Wild Boyz seem to have no connection to any other gang; they’re a pure product of Pine Ridge.

“Our clique is about our culture,” he says, “about being a man, and a warrior.”

Marty is the great-great-great-grandson of a Lakota chief named Red Cloud, a famous warrior and statesman. In 1866, Red Cloud began to beat back the U.S. Army as it was building forts in the heart of Lakota country in present day Wyoming. He helped secure treaties for the Indians and was the man who

settled the tribe here in Pine Ridge. Marty’s grandfather, Oliver Red Cloud, is the chief of the Oglala Sioux.

In Lakota tradition, Marty is expected to take part in a “sweat” tomorrow, a ritual of prayer and purification held in a sweat lodge, to prepare him for his first sun dance. The sun dance is a ceremony meant to purify the tribe. It represents life and rebirth, and for Marty it will also acknowledge his entry into adulthood. Marty’s best friend, Clayton High Wolf, who helped found the Wild Boyz six years ago, is the nephew of a Lakota medicine man and has invited Marty to dance at the ceremony, four days from now.

But if the dancer is not spiritually prepared, he may fail, and Marty is not sure he’s ready. He has an infant son and is estranged from the boy’s mother and at odds with her family. For the past few nights, visions of the woman have disturbed his sleep.

“I’ve been having these dreams about her showing up at our sun dance, and you know, them kind of dreams ain’t natural,” says Marty, blowing on the red ember of the joint. “And so there’s a lot of questions in dreams like that, and I gotta figure it all out.”

That night, Marty has the dream again. The next morning he drives out to the sweat but refuses to go in. The medicine man says the spirits are trying to tell him something and that someone may have put bad medicine on Marty. “The spirits told him I’m strong, and that the choices I make are my own,” Marty says. “My last name says it all, and it’s hard to carry. I’m a Red Cloud. I got to match my own powers. I got powers I can’t control. There’s times when hot water don’t burn. That’s ’cause I’m supposed to be something different.”

MARILYN WHITE, MARTY’S MOTHER, DOESN’T REALLY BELIEVE HE’S IN A gang. A friendly gray-haired woman who sometimes feeds the slots all night at the Prairie Wind Casino, she thinks Marty is just playing at being a warrior, staying true to his Lakota heritage. She doesn’t know that he has sold coke from time to time, that a rival once stabbed him in the ribs, that he’ll kick your face in if you fuck with him. That’s because Marty is a sweet-natured guy, polite, always throwing a sly grin. He also babysits his young nephews—the ones his drug-addicted sister abandoned.

“Oh, he wears that bear-claw tattoo,” Marilyn says. “But that’s just him and his friends. It’s more of a friendship thing. It’s more like, ‘I’ll stick up for you, you stick up for me.’ That’s what he told me.”

Marty sits behind his mother and chuckles. It’s a blistering Saturday in mid-July, and we’re in Marilyn’s airless office, a cement building next to a gas station. Marilyn works the front desk at the community health clinic, where she hands out condoms and keeps a supply of Pampers and tampons. If a local mother—say, one of the many 15-year-olds running around with a baby on their hip—can’t afford to buy these items, Marilyn will sometimes accept a little beadwork as payment.

Among the 314 Native American reservations in the United States, Pine Ridge is the second-largest and one of the poorest. Shannon County, where it is centered, has ranked among the three most impoverished counties in the country for the last 30 years. Home to the infamous Wounded Knee massacre site, as well as the descendants of Crazy Horse—who taught George Custer what it was to lose—Pine Ridge became known more recently as a battlefield of the American Indian Movement. AIM was the Indian version of the Black Panthers, bringing national attention to grievances like the Lakota land claims in the nearby Black Hills, which were stolen from the tribe after gold was discovered there. In 1973, AIM followers occupied the town of Wounded Knee for 71 days. Two years later, a pair of FBI agents were killed on the reservation.

An AIM activist named Leonard Peltier was convicted of the murders, sparking outrage from public figures such as Marlon Brando. Hollywood activists have moved on to other causes, but Pine Ridge continues to be a battlefield. Now the killers are unemployment (about 80 percent), alcoholism, drunk driving, domestic violence, drug abuse, and diabetes. Houses are falling apart. Doors are missing, windows are boarded up, garbage festers in yards. Grandparents often raise children in households of 20 or more because the parents are too drunk or just gone. The traditional Lakota language is in danger of extinction, the social fabric is in shreds. Now kids like Marty find themselves torn between the remnants of their own culture and a seductive new one imported from New York and Los Angeles.

“He spends all day sleeping, playing video games,” Marilyn says, casting a half-stern glance at Marty, who just shrugs. “The guys with the big chains. Thinks he’s gonna be a singer and this hip-hop tough guy. That’s not going to happen here. He wanted to be that. Now he’s 22. It’s over with for him. He has to make the choice of either working all the time or staying in his room watching those videos, watching how other people live.”

Marty’s 38-year-old half-brother, Willie White, slumps in an afghan-draped chair. A former high-school-basketball star, Willie was scouted by Dakota Wesleyan University but dropped out because he was drinking too much. He wears a ball cap low over his eyes and a pair of reflective sunglasses. While Marilyn talks, he slowly rocks back and forth.

“Marty can save himself,” Willie says. “But even then, what’s there to do here?”

“Ain’t shit,” Marty says, smiling. “Scads of nothin’, yo. Just chillin’ and that shit.”

THE TOWN OF PINE RIDGE HAS TWO STOPLIGHTS. ITS MAIN GAS STATION and convenience store, Big Bat’s, serves as hangout and gossip post for both young and old. Roughly 40,000 people live on the reservation, scattered among dry prairies and lush rolling hills. Most homes, like Marty’s, are single-story, without recent paint jobs. Marty’s home, despite the knee-high weeds and junked cars in the yard, at least has the benefit of a makeshift alarm system: a mangy and underfed army of dogs, one chained beneath each of the six windows. There are no street names around here, nor any need for them.

Everyone knows where everyone else lives. Pine Ridge is a dry reservation. It’s illegal to possess alcohol here. But just two miles over the state border to the south, in Nebraska, lies a small town called Whiteclay. Its downtown is only a few blocks long but is lined with four beer outlets. Between them they sell 12,000 cans of beer daily and pull in $4 million a year. The population of the town is 14. That does not include the dozen or so alcoholic Indians who sleep in the alleys and turn their haunted faces up at passersby, begging for coins or offering to trade rusted tools or their own tattered blankets for beer. Of course, most of the beer sold in Whiteclay goes straight to Pine Ridge. In early July a group of concerned Lakota planned to put up a roadblock to stop the flow of alcohol. But the police told them the barricade would be illegal, and after a brief argument, they abandoned the idea.

John Mousseau is the acting police chief on Pine Ridge Reservation, and he handles most of the gang issues. He’s a tall 36-year-old man with an easygoing manner who grew up on the reservation and who knows nearly every gang member, including Marty and his friends. Mousseau once shot and killed a gang member who had been firing an assault rifle out of a bedroom window.

This past March, Mousseau’s department broke up a coke ring on the reservation run by the Igloo Gangster Crips, or Iggy Boys, arresting 16 people. Meth is becoming a problem here as well. Last November, a 15-year-old girl overdosed on it and was found dead on a trampoline. Mousseau says that meth use on Pine Ridge is still mostly underground and very scattered. He doesn’t think the Wild Boyz or other gangsters are its main users, preferring, as they do, to dabble in pot and occasionally coke—something Marty and others confirmed.

“These guys are not bad kids, but they’ve chosen the wrong people to hang out with,” Mousseau says of the gangs in general as we drive through Pine Ridge on a sweltering day. “They break into vehicles and homes, steal stereos, DVD players, game consoles, clothes, anything they don’t own but want. And

they’re bold enough to go using them in public.”

Though Marty and his friends are nowhere near as dangerous as big-city gangs, it’s a mistake, Mousseau says, to label them wannabes. One former Wild Boy is on trial for a double murder that occurred on the Rincon Indian Reservation near San Diego, California.

“A lot of these guys, I’ve seen them grow up, played ball with their fathers or older brothers,” Mousseau says. “By themselves, when they’re not drinking, they’re good kids. When they get around other gang members, they start exhibiting the mentality, and that’s where the problems lie. Guy like Marty, I could toss a coin, fifty-fifty, where he ends up.”

VINNY BREWER IS 18 YEARS OLD, A HIGH-SCHOOL SENIOR, AND ALREADY Mousseau considers him a hard-core risk. The nephew of a police captain, Vinny is a quick study and a great basketball player. He is sensitive but rebellious. His friends say he could get into any college he wanted to. On this Monday night, Vinny wears a do-rag and a Winston-Salem jersey. He is surrounded by beer cans, and about to get his first Wild Boyz tattoo. We are in his mother’s house (Vinny says she’s out of town), which is full of photos. There is childhood picture of Vinny in Lakota garb and one of his grandmother as a young woman in deerskin, crowned Miss Indian America. The room fills with pot smoke as The Game blasts from a CD. There are a dozen Wild Boyz in the house, including a guy named James, a 24-year-old who will get depressingly drunk and cry poignantly to me later.

It’s not uncommon for young men, like the one above (left), to behave in one of two ways when they drink: They start fights or they start crying and threatening suicide. Fresh out of jail, this Wild Boy (right) took a handful of pills he could not name. They left him stupefied at a tattooing party (opposite) where Vinny Brewer officially became a Wild Boy for life. To view about his difficult life. Tomorrow he will point an assault rifle at me, telling me he’s “just foolin’—it ain’t loaded.” Another guy, a baby-faced 21-year-old named Gabe Dreamer, one of the more articulate and gracious of the gang (and Mousseau’s nephew), tells me how he once bashed a guy in the head with a baseball bat after he and a friend were surrounded by gangsters, one of whom was wielding a lead pipe. “I felt bad about it,” he says.

Just before Vinny gets his tattoo, I find him standing in a doorway, looking out into the dark country night as crickets chirp against the background of the party noise. Vinny says he first tried coke at 15, that he always wanted to grow up to make a change on the reservation, that he worries about the kids:

“The little girls getting raped at their houses—’cause their uncle rape them and shit, and no one does nothing about it.”

“It’s, like, every night before I go to bed I always pray,” Vinny says. “I always pray for a better day. Hopefully. But it’s the same shit every day. Same shit. Look at where we live, man. Everything’s fucked up. I don’t try to use that as an excuse, but shit is fucked.”

Vinny says it’s tough balancing his traditional beliefs with membership in the gang. Just a few nights ago, as he was driving through town, a rival gang came up and smashed his back windshield in, and Vinny has been thinking about payback.

“My Lakota culture is real important to me,” Vinny says. “But, like, now it’s lost to me because I’m drinking, I’m doing drugs. I respect my culture, man. I’m a culture guy. But right now I ain’t, because I’m doing the shit I’m doing. I ain’t proud of all that.”

Lyle Jack, a 41-year-old member of the Pine Ridge tribal council, says most gangs have so blurred the line between their culture and hip-hop, they no longer know who or what they want to be. “We need to show them that alcoholism, drugs, and violence are not part of our culture,” Jack says. “The warrior culture that they think is Lakota, is not us. It is not part of our four virtues: wisdom, generosity, fortitude, and bravery.”

Soon everyone is gathered around Vinny as he gets his tattoo, signifying that he will always be part of the Wild Boyz family. Afterward I ask him if he ever thinks of leaving the reservation, going to a city, where he can get a job and a new life. He surprises me by saying that’s his goal, but he’s sure he’ll drift back, like everyone else.

“We got all that land taken away, know what I mean?” Vinny says. “They put us on these reservations, gave us alcohol, make us stupid and shit. They left us in this hole and they all forgot about us. No one ever thinks about us no more. And now I’m a product like everyone of this system. Like all these guys, these fuckers. I’ll probably die here.”

Inside the house, I find Marty sitting in a corner, smoking dope, nodding to the music. This afternoon he had another one of his dreams. He was flying as his Lakota spirit, alongside his friend Clayton, and again he saw his ex-girlfriend.

“There were lots of signs around her,” he says, ones he didn’t understand and that he can’t explain. The dream rattled him so much he went to talk it over with his grandfather. His grandfather explained that it meant he wasn’t prepared to sun dance. “It’s not my time,” Marty says. “My grandpa say I’m not ready to be a man, and I got to respect my grandpa. He’s strong—he a Red Cloud.”

When we talk later that night, back in the living room, Marty doesn’t seem upset about it. His friends tease him, say he “bitched out,” but in fact, they, too, respect his grandfather’s interpretation of the dreams. “Next year,” they all tell him.